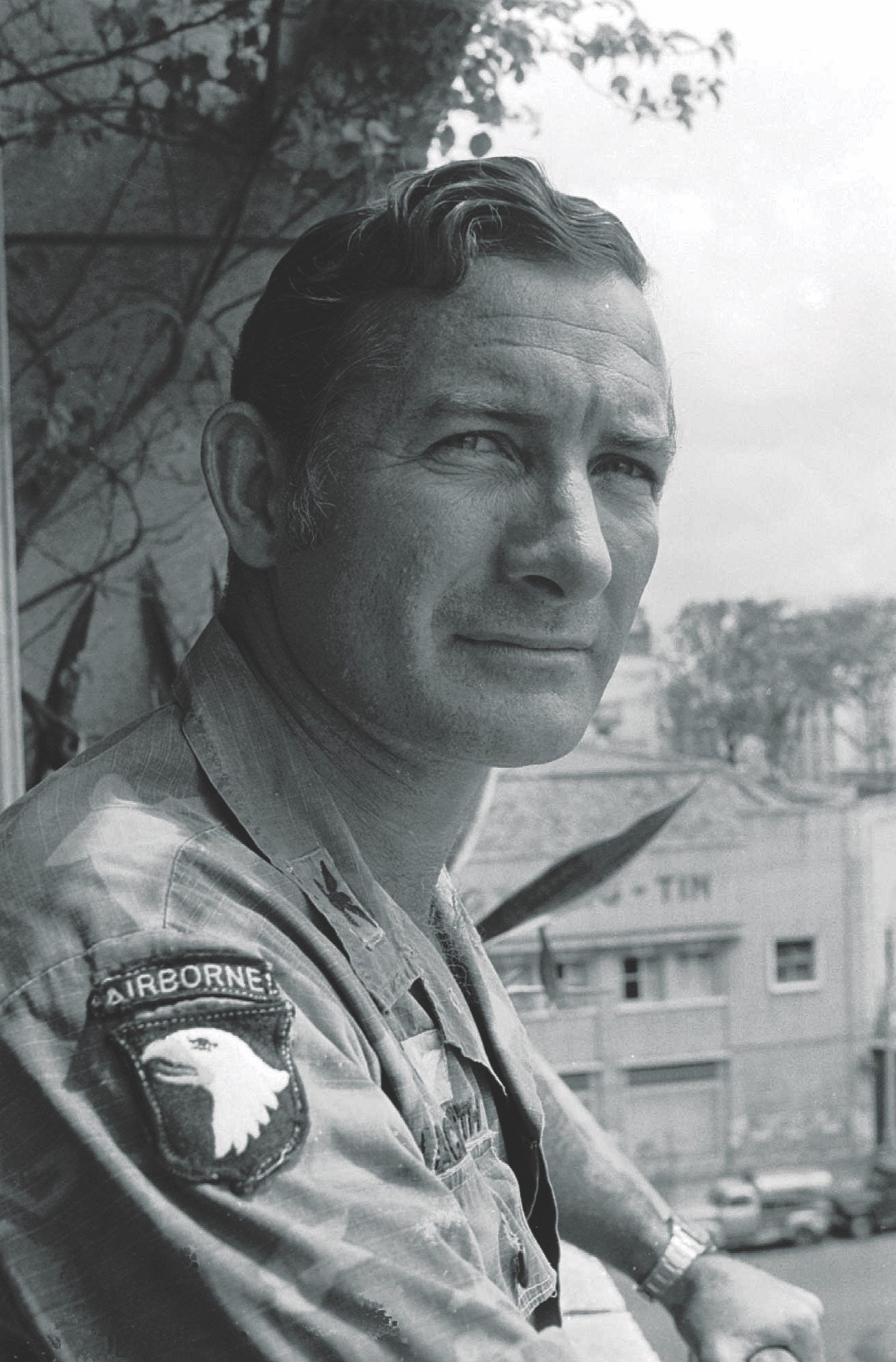

David Hackworth on Basic Military Training

And its Implications on National Policy Across the Board

This is the second piece in a series of articles discussing the standing of David Hackworth’s writings today. For the first, click here.

Just as last time, I will begin this essay with a few long-form quotes from Hackworth’s 1989 “About Face”:

“After WW II, a boy named Willie Lump Lump enlisted in the Army. He went to Fort Benning to take his infantry training, sixteen weeks of sweat and tears and lots of punishment, to turn him into a hardened soldier. Along about the seventh week of training, a sergeant stood up in front of his class and said, “Gentlemen, I’m Sergeant Slasher, and today I’m going to introduce you to the bayonet. On guard!” With that, the sergeant went into the correct stance for holding the bayonet. “On the battlefield,” he continued, “you will meet the enemy, and there will be times when you will need this bayonet to defeat the enemy. To KILL the enemy! Over the next weeks you’ll be receiving a twenty-four hour block of instruction on the bayonet, and I will be your principal instructor.”

Willie Lump Lump went back to the barracks, deeply upset. Man, that was so brutal out there today, he thought. The war is over. We’re living in peace and tranquility, and still the Army is teaching us how to use these horrible weapons! “Dear Mom,” he wrote home. “Today the sergeant told me he’s going to teach me how to use the bayonet to kill enemy soldiers on the battlefield.”

Willie’s mother was shocked. She got right on the phone: “Hello, Congressman DoGood? This is Mrs. Lump Lump. I want to tell you what’s happening down at Fort Benning, Georgia. Here it is, 1949, and they’re teaching my baby to kill with a bayonet. It’s uncivilized! It’s barbaric!”

The congressman immediately got on the horn. “Hello, General Playitright at the Pentagon? This is Congressman Dogood. I understand the Army is still giving bayonet training.”

“Yes, we are.”

“Do you think it’s a good idea? I don’t think it’s a very good thing at all. It’s even… somewhat uncivilized. I mean, really, how many times does a soldier need his bayonet?”

“Not very often, sir, it’s true. Actually, I was just reviewing the Army Training Program myself, and I was thinking that the bayonet is a pretty obsolete weapon. I agree with you. I’ll put out instructions that it’s going to stop.”

The next day, seven hundred miles away: “Gentlemen, I am Sergeant Slasher. This is your second class on bayonet training –“ The sergeant was interrupted by a lieutenant walking purposefully toward him across the training field. “Stand easy, men.”

“It’s out,” the lieutenant whispered.

“What!” said the sergeant.

“It’s out,” the lieutenant whispered again.

The sergeant nodded, his mouth wide open in disbelief. He returned to his class.

“Gentlemen, we’ll have to break here. It looks as if bayonet training has been discontinued in the Army.”

A year later, PFC Lump Lump, the model soldier, deployed to Korea with the 1st Battalion, 15th Regiment, 3d Infantry Division. He was standing on a frozen hill and the Chinese were coming at him – wave after wave after wave. Willie stood like a rock. Resolutely, he shot the enemy down. Suddenly he realized he was out of ammunition. He looked at his belt – not a round left. He saw a Chinaman rushing toward him. He remembered the first class on bayonet training. He reached down and pulled his bayonet out of his scabbard. Shaking and fumbling, he tried to fit it on the end of his weapon, but by that time the Chinese soldier was standing over him, with a bayonet of his own.

The Secretary of the Army signed his thousandth letter for the day: “Dear Mrs. Lump Lump: It is with deep regret that I must inform you that your son, PFC Willie Lump Lump, was killed in action 27 November 1950.”

Heartbroken, Mrs. Lump Lump wrote to some friends of young Willie’s in the company. “How?” she asked. “Why???” “Willie wasn’t trained,” they wrote back. “He didn’t know how to use his bayonet.” Now Mrs. Lump Lump was not only heartbroken, but outraged. She didn’t even bother to call Congressman DoGood. She barged right into his office.

“Why?” she cried and screamed. “Why wasn’t my son trained for war?”

The mythical Willie Lump Lump was my training aid. I used him in every unit I commanded, to explain two things to the troops: first, that the training they were about to receive was in their best interests, and second, that the civilian population didn’t know diddley-squat about the realities of war.”

The next few quotes are from when Hackworth was commanding a training battalion on Ft. Lewis. During the early stages of his tenure as commander, he pretended to be a private and attended the training to see what was actually going on in his command.

“As impossible as it seemed, I didn’t get caught throughout the entire masquerade, except the time one instructor was so incompetent and the instruction so bad that I blew my lid and my cover and took over the class myself rather than have the trainees lose valuable time and critical information. But the experience was mind-boggling, and unlike anything I could have imagined. Far from the prying eyes of superiors and non-Training Committee personnel, the AIT training I witnessed was criminal. Virtually everything these trainees got was wrong in terms of its applicability to the war in Vietnam. Meanwhile, the essential things were ignored completely, or given so little attention as to render them meaningless. During the instruction block on the M-60 machine gun, for example, I sat as dumbstruck as the befuddled young trainee beside me while a young instructor who’d never been to Vietnam covered in exceptional detail the making of range cards and the walking of the final protective line—both pretty useless in the jungle, where dense foliage limited vision to a few feet. When we got to the hands-on part where the trainees actually fired the M-60, I noticed most of them didn’t react properly to a misfire. Later, when I asked about twenty-five of these soldiers what the first step in dealing with a misfire was, not one of them had any idea. It should have been as second nature as throwing on the brakes to stop a car.”

“The four-hour block of instruction dealing with the “starlight scope” night-vision device was so technical and boring that when it was over I couldn’t remember even 2 percent of what was covered. Neither could my classmates. The impression the instructor gave was that it was so complicated that it was well beyond most of the trainee’s grasp; in fact, what the average soldier needed to know to operate this superb battlefield tool was so simple it could have been taught in no more than thirty easy minutes.”

“With mines and booby traps responsible for probably 50 percent of all U.S. casualties in Vietnam, one would have thought mine and booby-trap training would be a top priority in the Vietnam-oriented AIT—maybe thirty hours’ minimum, with the subject integrated into every other aspect of the training. On the contrary, exactly five hours of the entire nine-week course were devoted to these lethal devices: four hours on booby traps, which barely scratched the “need to know” surface for the soldiers who would confront them daily in Vietnam, and one hours on mines, and on the World War II M-21 antitank mine at that. It was unbelievable. Three years after the first U.S. doughboys learned about these devices the hard way and there wasn’t even a Vietnam-oriented mines and booby traps training film. There was no decent mines and booby-trap training aid, something like what I’d heard the Marine Corps had developed, a device that when “exploded” propelled a red substance that clung to the trainee like blood. As I wrote to General Pearson at DIT during this period of total shock, “almost every U.S. full colonel in Vietnam has an air-conditioned trailer, but we don’t have a training aid that could save legs and lives?” I simply couldn’t understand it.”

Hackworth goes on in this manner for quite a bit, but I think the reader can see the common theme, so I’ll be ending the quotes here. Much of the following applies specifically to the army, but before sending this piece out I asked individuals from every branch except for the navy about the subject, and they had similar concerns so I feel comfortable generalizing my criticism to the military as a whole.

Have things gotten better since Vietnam in this regard? No, no they absolutely have not. I made it a habit to tell new soldiers assigned to me to forget everything and anything that they were taught in basic training, because it was all so horribly done. For starters, the drill sergeants are much more restricted, and the training is much easier both physically and mentally. This means that most soldiers are arriving to their units unprepared to even follow orders at all, let alone think for themselves. Privates arrive still extremely sensitive and self-oriented, and cocky from being completely untested. Instructors are told to avoid swearing in front of trainees, let along yelling at them. I can remember being told that I would be “skull-fucked to death” if I didn’t figure out some task when I was in basic training. Believe it or not, I survived such horrible treatment, and figured out how to do whatever it was that I was failing at. You can donate to pay for my therapy here.

Now perhaps I wouldn’t be so annoyed about the feminization of BCT if the training itself was higher-quality. But, of course, it isn’t. For a stellar example, when I went through BCT during GWOT some years back, we received a single day of instruction to cover claymores and IEDs. ONE DAY! And the IED portion could really have been boiled down to, “if wire in trash: bad”. The privates I was assigned later didn’t even receive a single day of instruction of IEDs. In fact, one didn’t even know what an IED was! Perhaps some senior officer will argue that “The army is preparing for LSCO, so IED training is irrelevant”. This, of course, is not true, but I’ll respond anyways. Why did I receive zero training throughout my entire service on conventional mines then? Those sure do exist in LSCO. Where were they in training?

Trainees also do not spend nearly long enough on weapon systems other than the M4. Hackworth may have been upset at the training provided on the M-60, but during my OSUT cycle we did a day on both the SAW and M240 at once. For a weapon system that 1/4 of infantrymen in a fireteam use, you would think that it would be treated with some level of importance. Dividing the training in half, we spent more time on both S.H.A.R.P, (the army’s sexual assault prevention program), and E.O, (Equal Opportunity), training than we did on the M249. But at least my cycle fired a sim round out of an AT-4; none of the soldiers I got later had ever seen one.

One piece of training which I will admit has advanced, although I haven’t a clue why or how, is radio training. During my BCT, we received a half-day on radio usage, and this was one radio per four trainees. However, my soldiers thankfully received several days of training on the subject, so at least there’s that.

Some have made the argument that BCT doesn’t really matter because the majority of a soldier’s training will be done at their unit. This is true for the current time, yes, but if the United States were to enter a conventional conflict, soldiers would be sent directly from their entry-level training to combat. Even in GWOT I knew several people who were in Afghanistan or Iraq within a week or two of in-processing at their first units. It is also crucial that foundations are built correctly with regards to training; to learn something incorrectly the first time often ensures you’ll do it wrong for life. Thus, while it is true that the majority of a soldier’s knowledge is learned aside from BCT, to say that it doesn’t matter is just untrue.

Now, the subtitle of this essay is “And its Implications on National Policy Across the Board”. What do I mean by this? Simply put, the United States military is one of two things: incapable of creating a functional training regime for new recruits, or completely disinterested in doing so. This can be directly upscaled to an argument many of us have: is the United States government simply incompetent or downright evil? Either the United States military establishment has avoided creating a functional entry-level training program for its soldiers because it doesn’t view them as important, or it is unable to do so at all. Either the United States government has avoided maintaining proper border control because it has no interest in doing so, or it is unable to do so. Either the United States government has allowed crime to create “no-go” zones within its urban metropolises because it doesn’t care to actually reduce crime, or it has done so because it doesn’t know how to fight crime.

It is important for political thinkers to consider the question of incompetence or intentional bad governance. If the government of your country intends to do things well, (obviously this is a gross generalization), but is unable to, then you should assist it. If it intends to do harm, then you should resist it. Similar lines of thought apply to military men in modern times. If the military establishment is fundamentally interested in winning its wars, but is having trouble doing so, then perhaps you should stay in and help develop the army you wish to see. If the Pentagon has no interest in winning wars anymore, than perhaps you should try and tear the building down….

This ties in well with J Burden's recent show with Clay Martin where they talked about the destruction of military traditions like the Blood Rifles in the name of the "anti-hazing" crusade.