Prior issues in this series:

A brief abstract and explanation

For almost all of human history, mankind lived in societies which were governed mostly on the basis of custom and religion. When these societies had leaders, their roles were largely ceremonial and their power was limited in practice. Societies which are governed in such a fashion do not evolve or adapt quickly, often remaining quite similar for thousands of years. In light of this, societies which were not strictly governed in such a manner, (even where custom still existed), are a blink in comparison to the length of human history. Societies capable of thinking outside of the boundaries of custom are not a human universal; this is something often taken for granted. As such, we will be treating this government by custom as the “State of Nature” going forward in this series.

I realize that I am starting a series on a very specific political movement with a very “zoomed-out” look on human socio-political organization. However, I feel that starting from this perspective in important for two reasons.

Firstly, we tend to view history backwards, especially in these circles; a lot of us look for where things went wrong, so to speak. This creates a very biased perception of history which is no different from the way in which a Progressive thinks, only reversed. Instead of viewing the passage of time as inherently positive, we treat it as inherently negative. This warps our judgement of history and politics.

Second, we tend to view Progressivism as an isolated incident in political history, a unique movement. As I will demonstrate in this series, this is not entirely accurate.

The “State of Nature”

We must begin our discussion at the “State of Nature”. Man in nature is not an isolated individual, not even other primates exist in such a state. He has no claws, rather short and dull teeth, nearly no smell or night vision and a poor musculoskeletal system for an isolated existence. It can be inferred from biology alone that man has always existed in a society, let alone the anthropological and evolutionary evidence. This was common knowledge before the enlightenment: Aristotle famously stated that “man is by nature a political animal” in his “Politics”.

In this regard we can safely discard the theories of Locke, Hobbes and Rousseau when it comes to anthropological truth. Whatever one may glean from their works philosophically, this beginning with man as a solitary creature is a flaw scientifically. While these authors are mostly theoretical, a theory based on bad assumptions is typically a bad theory. Of course, I am implying that the intention of these thinkers was to be more literal than it likely was. However, these three have formed the basis for quite a bit of both enlightenment and post-enlightenment thought. As Francis Fukuyama states in his “The Origins of Political Order”, “..it is not unfair to contrast them with what we actually know today about human origins as a result of recent advances in a range of life sciences”. Beginning a study on the nature of man and the origins of political society from a solitary individual is just nonsense. Fukuyama refers to this as the “Hobbesean Fallacy”.

While it may seem like I am rejecting individualism as a concept here, that is not my intention, rather, I am explaining that there is no individualistic ‘state of nature’ as such. Instead, man has existed in a collective form for all of his history. The best comparisons that we have for how this would look are A) modern hunter-gatherer societies and B) Chimpanzees.

Chimps as an anthropological tool

Chimpanzees live in groups which average around one-hundred and fifty members. This number, known as “Dunbar’s number”, is an estimate of the optimal number of primates which can all recognize one-another in a community. While some Chimpanzee communities exceed this number, one-hundred and fifty is a good average. There is one dominant male in these communities, known as the “Alpha”, whose position is constantly in flux; with various males all competing against one-another for it. This competition is often more concerned with coalition building than it is direct violence. As said by Jane Goodall: “Males that form strong bonds and coalitions with others tend to rise higher in the dominance hierarchy and stay in power longer than those that do not.”

This model can provide a somewhat accurate picture for how early human communities may have looked. Humans and Chimps have an almost identical hormonal system and exhibit many similar emotional behaviors. The similarities in male-hierarchies between the two species have often been spoken of elsewhere, so it will suffice to say that these behaviors are also similar.

The Chimpanzee picture, however, is missing some key attributes. For one, religion is absent in Chimpanzees, although some researchers, (including Goodall), do believe that Chimps do signs of a proto-religious instinct. For another, we have reason to call Dunbar’s number into question with regard to humans, who have a much larger memory than Chimpanzees and are less smell-oriented with regards to remembering individuals. While there are still similar limits on the number of direct relations one human can have, our ability to abstract, (such as by using names), means that our communities can grow beyond direct relations. Due to these limitations, we must use other contemporary examples.

Modern primitive societies in anthropology

Something I must make note of here before continuing: most primitive communities now exist in contrast to the larger states which they either inhabit or border. Most of these communities are either largely uncontacted or voluntarily maintaining an ‘primitive’ way of life. Those who choose such a life usually do so precisely because it is different from a modern state. Perhaps the most important note from David Wengrow and Graeber’s “The Dawn of Everything” is that the ‘indigenous critique’ is as much a product of Native Americans intentionally contrasting themselves with Europeans as it is any real differences which European observers noticed between the two societies. As such, their use in an anthropology is naturally limited. However, these groups still must contend with many of the same sociological, psychological and natural factors and limitations as early man would have, so there is still utility in using them as an example. With regard to uncontacted tribes, most of these communities view themselves in a state of war with outsiders, and for most this war has been apocalyptic in proportions. As such, the culture and styles of governance which they have developed are biased towards a wartime function. Once again, with these factors taken into account, we can still take some conclusions.

Primitive societies across the globe share a similar sort of governance. Most are guided by a set of elders or “wise men”. These individuals’ primary purpose is usually the upholding of custom. Even when these communities do have chieftains, their power is often very limited in practice. As such, it is fair to say that most primitive communities exist in a semi-egalitarian manner. Most leadership positions are more ceremonial than material. In reality, custom and religion, (custom typically being based in religion), rule in these societies. This custom is typically maintained by the oldest members of the community, or those perceived to have a connection to the ethereal. Custom, however is also typically collectively enforced. If someone breaks with custom, consequences can be severe, not just for the individual but the whole tribe. Because of this, members of primitive communities are often quite strict with one another in this regard.

Early religion

I must also, of course speak on religion. Religion often enforces and exists in a symbiotic relationship with custom. Pork is not banned in two of the three Abrahamic faiths because of its metaphysical meaning, avoiding pork was custom in the Middle East before these religions were even founded and it was simply carried into them. Most of the old Testament is dedicated to either tracing lineage or describing materialist customs. Even before the faiths of the book, things like funerary practices, marriage law and warfare were largely regulated by religious practice.

From David Hume’s perspective, religion, (and by proxy, custom), provide a different way to maintain power over the community than our earlier Chimpanzee example. Rather than fighting or political maneuvering, interpreting the forces of nature allows an individual to exercise power in a relatively safe manner. The smartest man in the village could very easily discover this “ability” or “vision” and gain a much higher standard of living rather quickly. From this perspective, most shamans are quacks. What this means in practice is that they are using religion and custom as a way to guide or control, (same thing different connotation), the society around them. Because man is a religious creature, this works quite well. Religious practice very often comes with quite a threat behind it, one’s eternal soul typically means quite a bit to them.

I do not believe in such a cynical view of religion. While, of course, Hume is correct in assuming that a great many shamans or seers across the world are quacks, I view religion a great deal more charitably. For starters, the world is a scary place with a lot of things that we do not understand. Humans are naturally ritualistic, if we do X and then Y happens we like to associate the two. Perhaps the first of these shamans or seers saw the manner in which these proto-rituals were doing harm to their practitioners and decided to redirect them in a more productive or fulfilling way. This seems particularly likely with respect to the fact that sacrifice is one of the easiest rituals to form. Even this perspective assumes that the shamans and seers are largely unbelievers, which I doubt.

Most shamanic figures certainly believe(d) in the Gods. To be an atheist in modernity is one thing, to be an atheist in a world in which you have no explanation for rain is quite another. Often the “powers” that they possess are bestowed upon them by someone else at a young age; it may well be that most shamanic figures worldwide genuinely believe in their powers.

Lastly, the use of psychoactive or even psychedelic substances is older than our knowledge of human history is. These may have shaped proto-religions in ways that I can’t even begin to dissect fully in this essay. For just one example of the effect that these substances may have had, look into the shared attributes of sacred geometry worldwide. I believe that the impact of various mind-altering substances on religion are far-reaching.

Regardless of how religions were formed, most shamans and seers are still bound by the social customs they live within. These “quacks” as the cynical would call them are not free of custom themselves. For starters, even if they were truly as atheistic as the Hume-inspired would argue, they still must keep up a facade. More importantly, they are likely unaware of whether the Gods actually exist or not, and unaware of the true status of the other shamans within the society. As such, these individuals are only allowed a modicum of freedom from custom and thus only a limited amount of authority.

Furthermore, upholding custom is a collective task. Not only must it be practiced by all within the society, but all must be watched to avoid a breach of custom. In many societies a breach of custom could have serious consequences, going as far as death. Ritual punishments can often be extreme, humiliating or both.

These limitations prevent any one shaman within a primitive society from making any radical adjustments to the customs within the community. Radical changes in any practice could easily bring the wrath of the Gods down on a community, let alone the wrath of the community on its shaman. As such, generations of tradition were typically never revoked, only expanded upon in a series of growingly complex rituals.

The role of age and sex in primitive societies

In a society which is concerned primarily with upholding tradition, it is only natural that two groups of people matter quite a bit: the eldest and those who have a good memory. The purpose of the eldest is obvious, if tradition is maintained by following what was done before, then whoever can remember the furthest back is a crucial member of the community. Similarly, those with large memories often find themselves filling the role of oral storyteller—passing down lessons learned by the community’s ancestors. Storytellers occupy a crucial role in a variety of societies, both as entertainers and sources of information. In many societies, storytellers and shamans fill similar roles, often being the same individual. Additionally, many believe that pre-civilization man had a memory which was better trained than ours due to the lack of writing or recording. Because of this, it is likely that storytellers were often the same elders spoken about above.

Women also played a large role in the upholding of custom. A common theme found worldwide is that the sorts of communities spoken about in this essay dedicate quite a bit of their religious practice to the subject of fertility. In fact, fertility worship is so fundamental to most early religions that the first recorded religious practices concern it directly. Almost all religions which have high concern for female fertility and motherhood include women in religious practices, and as I have explained throughout this essay, those who are involved in religion are those who have the largest role in upholding custom. One small piece of evidence for this is the transition globally from largely matrilineal lineage-tracking to patrilineal.

A brief recap

To summarize so far: Early communities existed in a state of fundamental democracy based upon generational traditions which were led by shamans or elder figures but enforced both by and across society. These types of communities were semi-egalitarian, but power tended towards the elders due to the nature of generational tradition. Additionally, due to the nature of human priorities, fertility rituals or even fertility-centered cults often placed older women in the more powerful positions in the society, though this is not a universal. When I speak on “fundamental democracy” later, this is what I am referring to. This concept will be crucial further down the line. The irony, of course, is that such a state is largely based on tradition rather than nature, but we will still be referring to this as the “State of Nature” for the purposes of this essay.

Examples

I have made quite a few claims here, so if the reader is somewhat skeptical of what I have said thus far they are in the right. As a result, I must present a few pieces of evidence before we move on.

Fertility cults of old Europe

Before the arrival of the Eurasian steppe cultures into Europe, European cultures shared many of the traits I have described above. There were many cultures which rose and declined over this quite prolonged period, but I will be focused on one specific example: the Gravettian. This techno-cultural group is largely known for its Venus carvings like the one pictured below:

While the Gravettians produced other figurines, they did so at a much lower volume, leading researchers to suspect that these figurines had a religious connotation. Because the carvings tend to resemble the physical attributes of pregnant women, they are often used as evidence for a fertility ritual or even a fertility cult.

This techno-culture group dominated Europe for about 12,000 years before disappearing due to the Last Glacial Maximum. They lived largely in either caves or mammoth-hide shelters. As implied by the era, they lived mostly off of the meat from hunting megafauna.

Like many other groups in Old Europe, they used Red Ochre on many of the few individuals whom they buried. This was most likely a form of ritual. Some burials even contain jewelry. This group is also credited with the first ceramics.

Okay so why am I mentioning the Gravettians? Well, a few reasons. First of all, the biggest symbol that they have is that of a fertility goddess, or at least a figurine symbolizing fertility. A common trend within societies which revere fertility to such an extent is that women play a large role in the religious side of things, (at least with regard to the fertility god/goddess). Because this is the only symbol which the Gravettians produced in such high quantities, one assumption that could be made, is that women may have had a large role in the ritual activities of these people.

One trend that anthropologists and archaeologists have observed worldwide is that with the rise of the state-based civilization came a transition to worshipping more male deities, often concerned with warfare or the hunt rather than fertility. This trend will reappear as we discuss other culture groups.

The other thing I want to take note of regarding the Gravettians is a general lack of evolution during their existence. While it is often treated as a result of technology, culture also plays a large role in change within a culture’s behavior. For example, Tasmanian natives were isolated for over 10,000 years, but did not develops even rudimentary boats or fishing technology. The Gravettian culture existed for around 12,000 years, yet it remained largely unchanged across its archaeological record. This trend will also reappear.

Çatalhöyük and the proto-city

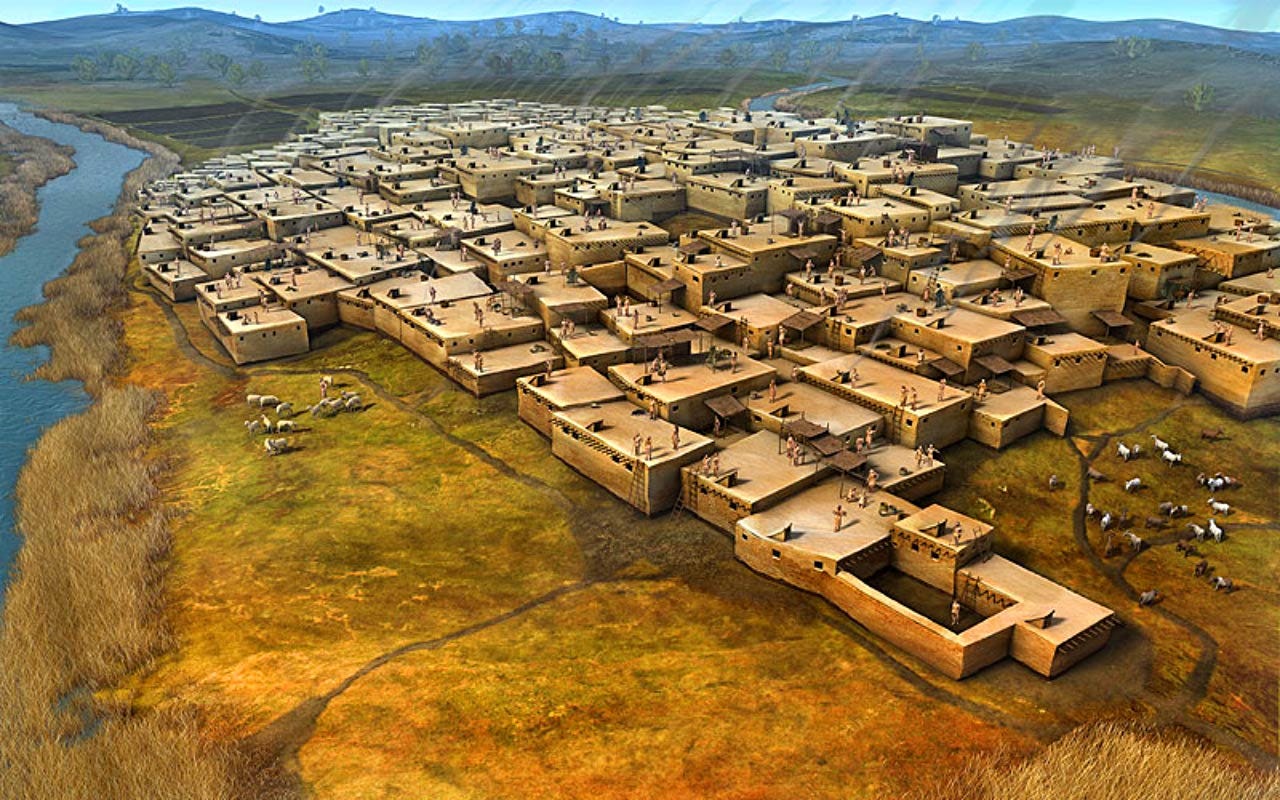

Çatalhöyük, (cha-tal-hoo-yuk), is a proto-city which existed in South-Western Anatolia, (Turkey), for about 2,000 years. This settlement is unique in that it existed before many thought that human civilization at such a large scale did. The city has no known public structures, (temples, palaces, etc.), but has a large variety of homes. These structures were not standardized in size, but the differences in between them are not believed to have come from any social stratification, but rather space limitations due to their construction style, (pictured below).

Like the Gravettians, these people made large numbers of Venus figurines, and it is believed that these had religious significance. They also carved bull heads into many of their walls, leading many to believe that cattle also had spiritual significance for them.

The people of Çatalhöyük are significant for this discussion because they were practicing agriculture and living in a large scale society with very limited evidence of stratification. What this means for us is that social stratification may not be an immediate consequence of living in a large society nor the technology of agriculture. Instead, stratification may be a way of life which arises through a cultural shift, not a technological or size one.

!Kung people

The !Kung, (Pronounced Kuung or Coong), are a band-structured group who live in the Kalahari desert. While many now live in local villages, traditionally they live in small bands which frequently migrate. Their religion is complex, but for our purposes I will note two key attributes. First, they use psychoactive substances to induce a trance in their healers. Second, the majority of the population is believed to have some level of healing ability. This status of healer is the only official position which consistently exists—in times of duress they may appoint a chieftain but he or she has no more power than any other elder.

The !Kung have many odd practices and beliefs which are worth studying, (I recommend a read through the linked Wikipedia article), but I predominantly chose to list them as an example to demonstrate this relative lack of hierarchy. The status of healer is so common throughout the society that any material advantage it may have is spread across over half of the population, and any chieftains are appointed on a temporary and limited basis. Additionally, the !Kung provided the model for the perceived sexual egalitarianism which many believed a universal among hunter-gatherer societies until quite recently.

The Yanomami

The Yanomami, (pronunciation obvious), are a tribe which live in the Amazon on the border between Venezuela and Brazil. They have lived here since at least 1654, and are an example of what I meant when I said that most of the primitive societies today have experienced apocalyptic wars with the nearby civilizations. The first major contacts Europeans had with tribes in the area were largely slave raids, and in the modern age armed groups have fought with them over gold, lumber and land. The Yanomami have also frequently had to deal with epidemics of diseases brought by either European contact or even contact with other local peoples in modern times.

While it is unclear what role was played by these events, what is certain is that the Yanomami are very violent by modern standards. Around half of all Yanomami males die violently. Yanomami engage in a large degree of domestic abuse, (very unique among the examples here), and often commit rape or massacres in warfare. They typically engage in either ambush or raid warfare like most groups of a similar subsistence strategy, leading to few survivors.

While many who study the Yanomami claim that their violence is largely a symptom of interaction with Westerners, I disagree. For starters, Mesoamerican civilizations weren’t exactly known for their peaceful nature. For another, most of the conflicts that the Yanomami engage in is either with other Yanomami groups or other indigenous tribes, and they often fight over more symbolic issues or perceived spiritual offenses than resource conflicts. They’ve also been engaging in this level of systemic warfare for longer than most modern states have existed, so I think there’s definitely more to account for than simply outside influence.

Additionally, Yanomami men consume psychedelics almost daily. They do this for a variety of ritualistic reasons, the largest being as a form of prayer. To really understand the effects on culture of this sort of ritualistic usage of mind-altering substances, I highly suggest watching this video on the tribe, although I believe that this particular group is a bit domestic. An interesting little note here, the Yanomami consume these substances in a powder and speak a Carib language; Columbus notes that the Taíno people of the West Indies did something quite similar. The Carib language was predominantly spoken on the North Eastern edge of South America.

The Yanomami present a unique twist to the Noble Savage myth put forward by many who are critical of Western-style civilization. While it is true that the Yanomami have endured warfare and other negative influences from the outside, they have maintained a level of violence both amongst themselves and outsider which can only be described as systemic. Despite this, they also have little in the way of a standardized hierarchy, (aside from that of the husband over the wife), and live in collective housing which provides little in the way of material advantage.

The Yanomami represent a bit of a mix between the type of custom-bound society I have discussed above and that of one similar to the Chimp-hierarchy at the beginning. While custom and religion play a large role in their governance, martial prowess also does factor. Yanomami headmen are typically older influential men, but they were typically feared warriors in their younger years. Despite this proclivity towards a hierarchy of violence, tradition and custom still provide very strict boundaries on conduct; headmen still require a group consensus with the backing of shamans before taking any major action.

Summarizing these examples

The purpose of these examples wasn’t to praise or critique these cultures individually, but to demonstrate the result of custom’s restrictions on a variety of population groups. The largest trend to observe within these societies is that they have very little in the way of evolution over a massive span of time. The shortest of these cultures is the Yanomami, but even their span in the region is at least a thousand years. Additionally, a culture’s existence within a region is not necessarily the origin of this culture, just its presence in one location. For example, the Gravettian culture evolved into the Solutrean, which lasted several tens of thousands of years in its own right.

I presented the Yanomami as unique amongst the group because they are known to engage in warfare regularly, (although Gravettian burials show signs of violence). This is very important because there are many in anthropological circles who argue that early human societies did not engage in warfare frequently, or that societies with limited hierarchies are inherently peaceful. This has no historical backing. Additionally, there are those who argue that warfare and its needs ended this semi-egalitarian or unstratified way of life, forcing people to create strict hierarchies to match the needs of warfare. While this premise is somewhat more coherent, it is also incorrect. Lastly, the idea that the agricultural revolution ended this phase in human history has been very popular over the last several decades, but cases such as Çatalhöyük, (and a great many others), demonstrate that this is not necessarily a human universal.

So to recap once more: mankind’s “State of Nature” as I will call it is that of a society which is semi-egalitarian and heavily bound by custom. This custom is often directly religious but sometimes is respected purely on the basis of tradition. These societies largely do not make significant changes over even massive spans of time.

So this leaves us with a huge lingering questions: what happened to end this phase of some culture’s history? Why did it not happen universally? Do societies revert back to this way of living, or is the transition out of it permanent? This will be covered in the next iteration of this series.

Looking forward to seeing where this goes.

Take as many words as you need, short attention span chuds should seek Canadian health care.

I think any comparison of chimpanzees to human society is not complete without mentioning bonobos. At the very least because bonobos are the common retort from the left to using chimpanzees as a reference to a primordial human social model. I don't think it changes anything here, since the thesis is of primitive egalitarian, if still male led, societies. And bonobo research is quite limited (due to a much smaller geographic range)