Prior issues in this series:

Introduction:

As we discussed in the last chapter, for most of our history humans have lived under the strict rule of custom-based society. This society typically exists as either a fundamental democracy or a short-lived oligarchy of the elders. Such societies are defined by the understanding that what is ancient as good; in other words they are preoccupied with emulating the ancestors. Custom is all-encompassing.

This, however, is no longer the case. Instead, we have the concept of nature, which is something different and opposed to custom. Things can be both new and good, freeing us to choose paths which are different from those of our ancestors, with ideas instead being informed by what is thought to be natural, (with good and bad results).

The fact that we have arrived in such a state is not something to be taken for granted: the realization of nature as something different from, and unaffected by, custom originated from one source and spread throughout Western culture. This essay is to discuss the process by which this happened.

A crucial note on fertility cults

This is a concept which I should have elaborated on in chapter 1, but will add here rather than editing it into the last part since most of my readers won’t be going back to review it. In primitive societies, fertility is often a grossly misunderstood concept. The connection between child and father is much less obvious than that of child and mother—paternity is less easily recognized that maternity. Some feminist authors have suggested that primitive societies may believe that the mother is the sole parent, but I believe that this is a stretch for a number of reasons. However, there is quite a bit of evidence that the “Partible Paternity” belief is present in many primitive societies.

The partible paternity belief is the idea that multiple men contribute to the formation of a child. This belief can take a number of forms—I read of one which has been difficult to find now that occurred in Micronesia in which the belief was that the semen actually turned into a child, and therefore the woman had to be quite literally filled with it in order to produce one. Some other societies believe that while a woman is pregnant, each man she has intercourse with gives his traits to the child, so the mother has intercourse with a great deal of “fathers”.

Societies which have beliefs of this sort are more likely to be both matriarchal and matrilineal, (lineage cannot be traced through unknown fathers). These are the sorts of societies which tend to have fertility cults or rituals, and the ones in which the deities are more female and concerned with fertility. Old Europe is just one example of this.

One crucial aspect of these societies which I believe many have overlooked is that, (to my knowledge), no society which believes in partible paternity is also pastoral. This is likely because pastoral societies both observe and often interact with species during their mating cycles. Not only does this effectively ensure that they understand pregnancy to some level, but it also likely ensures that they understand paternity, (if a stud horse escapes to the mares only once, many may still become pregnant).

Once the concept of paternity has been understood, so too, (roughly), can the concept of trait heritage. If a mare is bred with a stud who is fast, the colt is more likely to be a fast horse. This opens the door to selective breeding techniques, a subject we will return to later.

On pastoral warfare.

As we discussed in part one, custom-bound societies are typically egalitarian within their own group. However, these groups are still bound by the same laws of resource scarcity as any other population, meaning that warfare for material reasons such as hunting grounds still occurs. This is typically more common in areas in which resources are particularly scarce—places like the Eurasian Steppe, mountainous regions like the Himalayas and deserts such as the Gobi. Those living in these regions cannot survive off of settled agriculture like those in more temperate climates, instead they live off of herd animals or even large-scale hunting. The pastoral lifestyle in particular is much more conflict prone—animals are much easier to steal than land is. Pastoral peoples are also semi-nomadic as the animals must be moved to new grazing grounds, leading to conflict with peoples who may already be living there.

Because of this resource competition, pastoral communities have historically been more prone to violence than agricultural peoples. This is reflected in their religious beliefs: steppe peoples often worship Gods which are related to war or dominance, and their rituals often center on preparation for war or the hunt. Warfare was a large part of these peoples way of life—for some it was their way of life. There is a famous Berber proverb: “Raiding is our agriculture” which explains this mentality. For those living on the periphery of settled areas, living off of the labor of others was a fairly reasonable choice.

Raiding other pastoral communities can be profitable, but also more difficult because your target is mobile and likely to be well-versed in raiding themselves. Raiding a settled population, however, may come with reduced risk. These populations are significantly less likely to be well-versed in warfare. They also remain in one location, meaning that they can be observed for long periods before the raid itself. Depending on where their crops are located, they can even be taken in a primitive siege.

Consistent raiding of a settled population, however, leads to its own problems. To shorten this segment of the essay, I will quote at length from James C. Scott’s “Against The Grain”:

“There is a deep and fundamental contradiction to raiding that, once grasped, suggests why it is a radically unstable mode of subsistence, one that is likely under most circumstances to evolve into something quite different. Carried to its logical conclusion, raiding is self-liquidating. If, say, raiders attack a sedentary community, carrying off its livestock, grain, people, and valuables, the settlement is destroyed. Knowing its fate, others will be reluctant to settle there. If raiders were to make a practice of such attacks, they would, if successful, have killed all the “game” in the vicinity or, better put, “killed the goose that lays the golden egg.” Much the same is true for raiders or pirates who attack caravans or shipping lanes. If they take everything, either the trade is extinguished or, more likely, it finds another, safer route.”

“Knowing this, raiders are most likely to adjust their strategy to something that looks more like a “protection racket.” In return for a portion of the trade goods, harvest, livestock, and other valuables, the raiders “protect” the traders and communities against other raiders and, of course, against themselves. The relationship is analogous to endemism in diseases in which the pathogen makes a steady living from the host rather than killing it off. As there are likely to be a plurality of raiding groups, each group is likely to have particular communities it “taxes” and guards. Raiding, often quite devastating, still occurs, but it is most likely to be an attack by raiders on a community protected by another raiding community. Such attacks represented a form of indirect warfare between rival raiding groups. Protection rackets that are routine and that persist are a longer-run strategy than one-time sacking and therefore depend on a reasonably stable political and military environment. In extracting a sustainable surplus from sedentary communities and fending off external attacks to protect its base, a stable protection racket like this is hard to distinguish from the archaic state itself.”

(Yes I did finally learn how to use the quote feature.)

To summarize so far, a community of raiders begins to live parasitically off of their agricultural neighbors, a practice which continued even after the founding of large-scale agricultural states such as in China or Byzantium. This begins to look more like a protection racket than direct warfare—ideally the raiders no longer have to raid the settled peoples at all.

This way of life is limited by the fact that the settled peoples may eventually succeed in throwing off such a racket, perhaps by becoming violent themselves. For some raiders, maintaining a geographic separation from their tributaries becomes either tedious or redundant, better to live amongst them to ensure no ideas of rebellion ever arise. This is the material side of a phenomenon which occurs all across the world, but there is an element missing from this before we can arrive at a society which can truly be above mere custom.

A brief detour into sociology.

In sociological terms, deviance refers to any behavior or action that violates established social norms and expectations. This behavior, while it obviously causes issues, is an important tool for social change. By demonstrating that the rules can be broken, the groundwork is laid for considering whether a rule should be broken or even exist in the first place.

Deviance is a human universal—even in the custom-bound societies discussed above. Of course, deviance is also universally an issue for whatever group is controlling the society. In the case of the custom-bound society, it is largely an issue for everyone because all actions are thought to be connected to the will of the gods or the ancestors.

Another human universal is the fact that the most deviant group in any population is the adolescent males. This stage of rebellion mostly stems from effort to insert themselves into the male hierarchy, (see chapter one), with effort to impress females being a close second. For both efforts, those who feel that they cannot compete successfully in the standard hierarchy are likely to behave in the most deviant fashion; trying to find ways to gain status outside of the traditional methods.

For an example that most of you can recognize: imagine the nerd of the 70’s and 80’s. The ‘nerd’ archetype hasn’t stopped caring about status, but he has realized that he can’t compete traditionally. Maybe he’s ugly or small or has a slight dose of autism. Whatever it is, it keeps him off of the football team, out of the cheerleaders and generally ostracized. Because of this, he devotes himself to dork intellectualism or something in STEM. When he’s able to turn this into a profit, he will have a place within the hierarchy, but will not attain it in the most culturally respected fashion. Obviously this has flipped a bit now, but there was a time when being a nerd was weird and icky.

In a custom-based society, (particularly the fertility cults of old Europe), the behaviors associated with being a young man full of vitality would be deviant. Using force or the threat of force to get one’s way would be heavily frowned upon within society, and taking any sort of position of serious authority would be taboo. As such, young men would essentially be brow-beaten into behaving within a strict moral framework.

Societies throughout history have searched for safe outlets for deviance. This has often been found in seemingly subversive rituals, in which behavior which is typically forbidden is allowed. In antiquity, examples of this were the Dionysian mysteries or Saturnalia. These rituals share in their obviously democratic nature, overturning the very hierarchical nature of the societies they occurred in. Saturnalia was largely a break in justice for Roman law, a pause in what was otherwise a very structured system.

For even earlier societies, it would be somewhat reversed: the sorts of commanding or violence which could be expected in antiquity would be largely forbidden. Because of this, the kinds of rituals used to allow breaks of deviance would have been more focused on providing an outlet for things like the use of force to get one’s way, or perhaps even a tyranny based in force. The “Killing of the Divine King” is one example of this. Another is the Kóryos.

The ritual that changed the world

The Kóryos was a band of young men who were sent away from their tribe for various periods of time. During this period of isolation, they would partake in raiding and other forms of low-intensity warfare against other groups nearby. This period of isolation may have lasted anywhere from six months, a year, or even permanent, (perhaps as a way of getting rid of an excess of men if women were in short supply and/or getting rid of problematic characters).

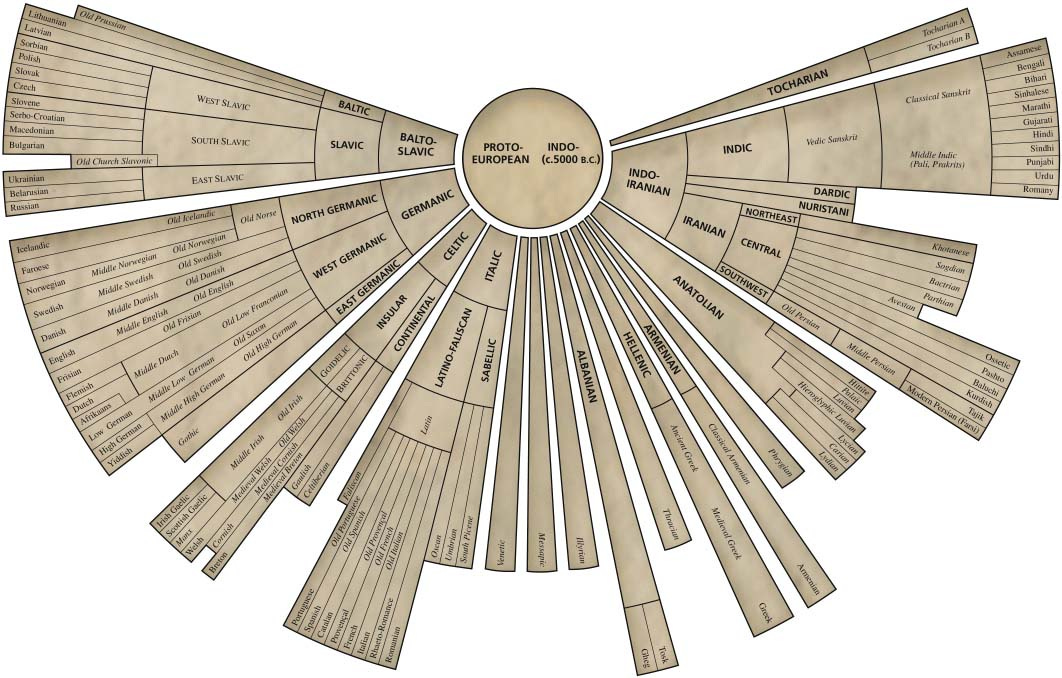

This tradition originated with the steppe herders from Eurasia. It spread westward into Europe, South into India, and even East into parts of China. Wherever steppe warriors went, they replaced large swaths of the male population and greatly changed the culture. Kristian Kristiansen, (whose work is referenced in other parts of this essay), stated that he is “increasingly convinced there must have been a kind of genocide.” These young warriors, often on horseback, were able to cover huge amounts of territory and, like most neolithic and early Bronze Age populations, were excellent navigators.

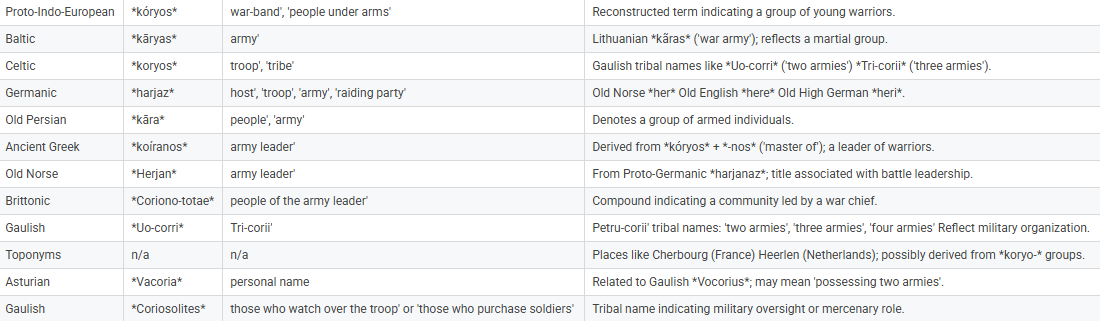

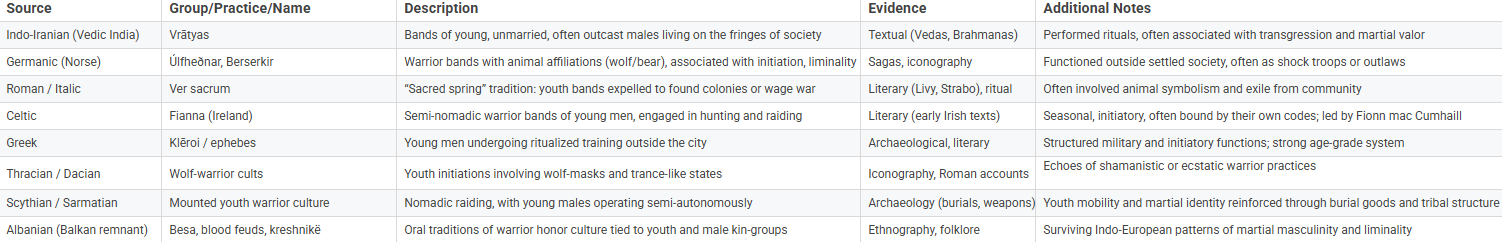

We are aware of the Kóryos for three reasons: linguistic, cultural and genetic. Linguistically, several Indo-European languages have words which describe similar phenomena, (see the table below for details). Many of these examples refer to specifically groups of raiders, not an army. Others refer to smaller organizations within a military organization, and still others refer to groups which no longer existed, (such as in village or tribe names). Culturally, many societies across antiquity had similar organizations which achieved a similar purpose, (once again reference the table). These various institutions contain several commonalities. First, most involve taking a group of youths and separating them from the rest of society. Second, many involve a kind of raiding or warfare. Third, many invoke some sort of wolf-like imagery.

Lastly, there is genetic evidence. Smarter geneticists than myself have done the math over the years, (many in a politically-charged attempt to disprove the idea of a male conquest of Old Europe). The data demonstrates an almost entirely male conquest of most of Europe, meaning that the introduction of steppe peoples into the region was a martial conquest rather than a peaceful migration of whole tribes. This ties in specifically to the Kóryos due to the unlikelihood of entire male populations simply abandoning their own tribes, women and children. (Two documents explaining the genetic evidence are here and here.)

There is also genetic evidence that the native horse populations of Europe were replaced with horses from the steppe around this time. The journal article I am referencing is particularly solid evidence because it simultaneously proves that modern horses originated from the steppe and disproves the idea of a mass migration with large herds coming from the steppe. (If you would prefer to read about this article instead of reading the whole piece follow this link.)

(As fascinating as I find this institution, (and this period of history in general), eventually I have to get this series to the topic of progressivism, so I won’t be exploring the topic of the Kóryos any further than necessary. However, if you are interested in the subject, some of the papers/books I used for research are located here, here, here and here. The book, “The Rise of Bronze Age Society” is also quite relevant.)

The institution of the Kóryos presents a unique solution to some of the problems mentioned in the sociology section. Through this ritual, young men in their most problematic stage are sent out from the tribe for an extended period of time. When these young men return, (and many won’t), they are integrated into the group of men. Much of the angst of adolescence will have been expended or put off by the transition back into society, and these men will have lived in a liminal status which symbolically “ends” this rebellious period.

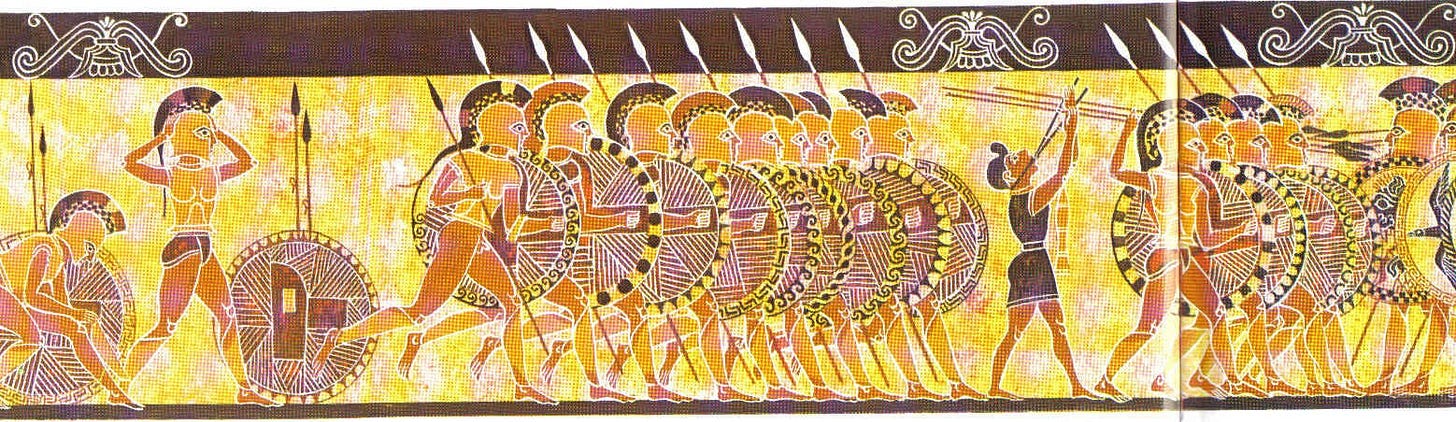

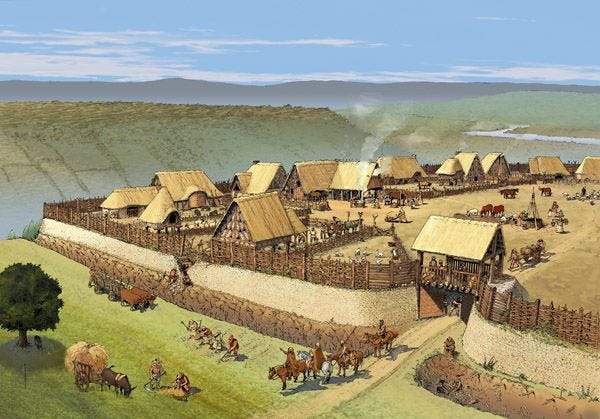

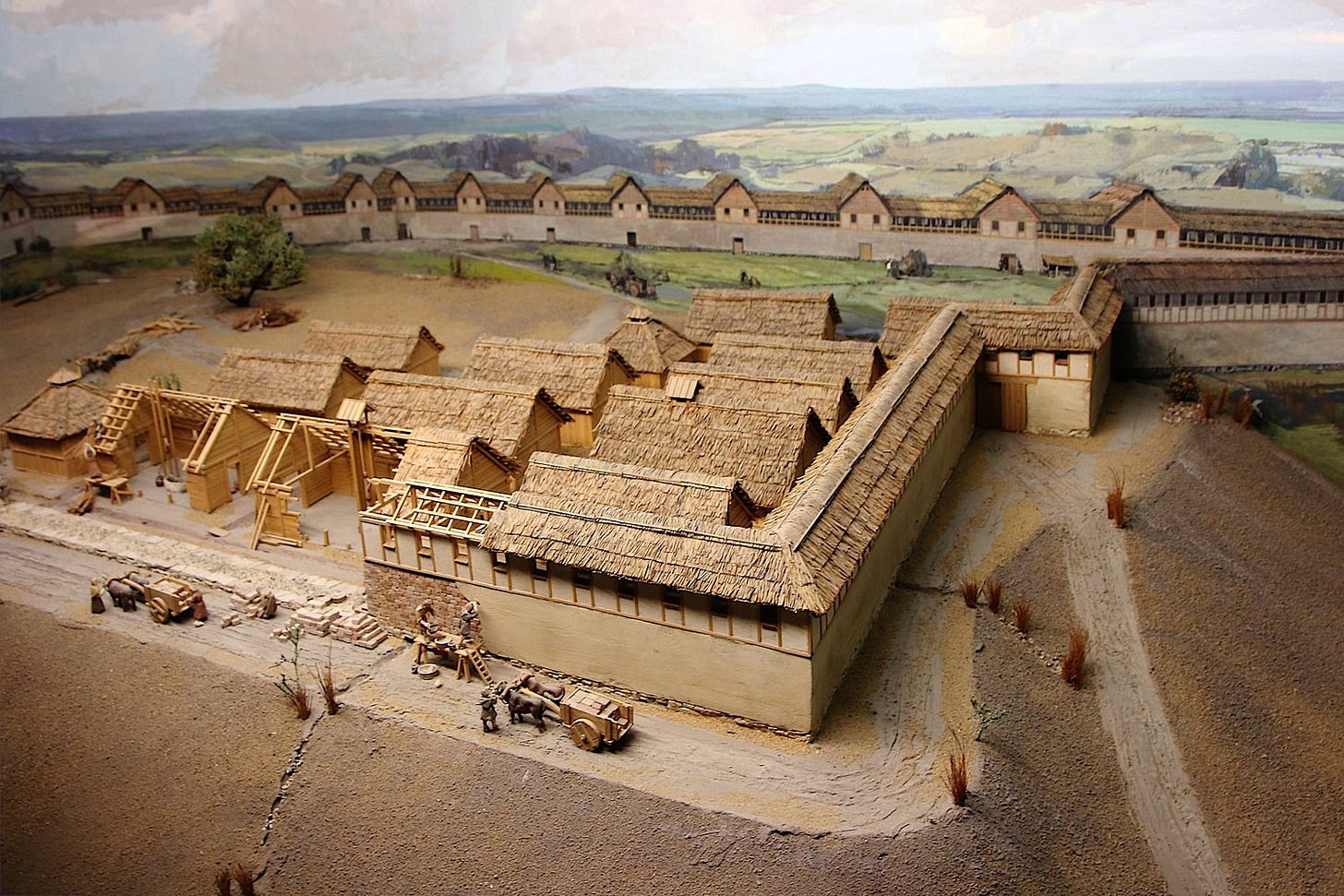

The tradition of the Kóryos had a potentially unplanned side effect: it allowed these young men to interact with other tribes or bands in further lands. The tribes which the Kóryos originated had been fighting one-another before in the same fashion as the Kóryos—raiding and ambush warfare. This way of fighting minimized casualties and enabled quick acquisitions of resources. This becomes more difficult, however, when fighting agricultural peoples. These people are much more likely to build fortifications, and their crops are harder to steal than livestock. Because of the fortifications, the youths of the Kóryos would likely have to fight the entire settlement rather than one or two watchmen, (primitive fortifications mostly served to delay an attacker so that the settlement could rally its fighters). This meant that in order for a Kóryos to raid an agricultural settlement, a significantly higher portion of the male population would have to be killed.

Agricultural peoples do have several disadvantages against pastoralists. They tend to be smaller and have weaker bone-structures due to their diet. Agriculturists also tend to have less experience with warfare, (they don’t raid as often, instead fighting in rare but larger battles). They are significantly less likely to have domesticated horses, giving raiders a huge advantage if a settlement is unfortified. Because of these disadvantages, a particularly strong Kóryos could find raiding them worthwhile in spite of the potential fortifications and larger number of combatants.

There are two possibilities for what comes next. First, a particularly strong Kóryos finds itself unable or unwilling to return home at the end of its time of isolation. Second, a Kóryos returns home with a new idea for subsistence: enslaving agriculturalists. Slavery, (at least in a temporary or symbolic manner), likely existed before the break from custom-based rule. Numerous tribal societies worldwide practice some variant of it, although whether they created it or inherited the institution is debatable. It is also perfectly plausible that a Kóryos is left isolated from its band. As mentioned above, some forms of the Kóryos may have even been designed to expel the young men so that they could find women and create their own band or tribe.

I view the isolated Kóryos theory as the more likely of the two. It makes more since linguistically, (a number of similar words in the Indo-European language family refer to bands which either do not return home or serve a permanent role). It is well-evidenced genetically, culturally, and also provides a much better explanation for what comes next.

On aristocracy

“A hereditary member of the British House of Lords complained that Prime Minister Lloyd George had created new Lords solely because they were self-made millionaires who had only recently acquired large acreages. When asked, “How did your ancestor become a Lord?” he replied sternly, “With the battle-ax, sir, with the battle-ax!” -Steven Pinker in “The Better Angels of Our Nature”

When the men of the Kóryos seized a settlement from the agriculturalists, as mentioned before, they would have had to eliminate a significant portion of the male population. Were a Kóryos unwilling or unable to return to their own people, they would almost certainly take wives from the conquered population, likely opting to remain where they were rather than continue to be fully nomadic.

Custom-bound populations tend to view groups of people as entities in of themselves. As explained in chapter 1, the way of a people is viewed as no different from the way of a deer, it’s simply how things are done. As such, the conquering populations will continue to live in the same, or a similar manner to how they always have, (most of the Gods of antiquity are evolutions of Indo-European ones). They will also keep themselves mostly separate from the male population of the conquered, (in terms of intermarriage). Because pastoral peoples are more likely to track lineage through the male line, this would not interfere with the practice of wife-taking initially. However, the conquering population, which understands lineage and selective breeding, will not intermix with the people of the conquered when it can be avoided, instead preferring to marry amongst themselves.

This process is the creation of an aristocratic regime. It occurred worldwide in a great number of societies. Whether we’re discussing the caste system of India, the various dynasties in China with nomadic origins, the Spartan regime, or even the Tutsis and Hutus in Rwanda, various peoples worldwide have inserted themselves as a ruling class over conquered populations. Most of these, however, are not done through a Kóryos-like manner, but involve migrations of entire groups of people, leading to a larger genetic difference in between themselves and the new underclass.

Such a system is the beginning of caste or hierarchy. Over generations, genetic differences cease to be quite as pronounced, (although still detectable in some populations, such as India, or Rwanda), but the premise behind aristocracy remains. Even in societies where the aristocracy is overthrown, it tends to be replaced by a different population group of a similar nature who enact the same principles as the group that they replaced, (Brahmins and Kshatriyas traded status throughout India’s history for example).

Philosophy and the idea of nature

The existence of aristocracy laid the groundwork for the creation of philosophy in four ways. First, it allowed a class of people to live without participation in the day-to-day labor of society, enabling aristocratic recreation, much of which was cerebral. Second, it severed some of the ties with custom with the creation of altogether new states. Third, it demonstrated a clear difference between people which largely originated through their birth and lineage, not their customs and religion. Lastly, it introduces differences in between customs which are contradictory in ways which demonstrate serious flaws.

Allowing the aristocratic class to live parasitically off of the conquered population meant that a great deal more time could be dedicated to ‘higher’ culture. In these societies, art tends to flourish, as well as literature. It’s no coincidence that almost all of the first literate societies had an aristocratic class. This leisure is not to be mistaken for the time-wasting way in which we think of leisure today, but rather consisted of preparing for war or counsel. Imagine it as the difference between having utility workers and having time to read or conducting all of your maintenance yourself. In having an underclass which performed manual labor, the aristocratic class was free to engage in other pursuits.

The creation of altogether new states or even perhaps new tribes separated the young men of the Kóryos from their elders. This meant that this martial class was left to carry on the traditions of their societies, greatly changing the nature of ritual and custom for these peoples. In many cases, the conquering populations absorbed some elements of the conquered’s culture or religion, or perhaps integrated the two. This is evidenced in the various “old gods” in European pantheons or demons in Hinduism, representing the conquered population’s Gods which were not to or could not remain. (Some theorize that the Goddesses of many pantheons are the older matriarchal goddesses which were symbolically married to the male Gods of the conquerors, such as Aphrodite and Apollo).

This alone could weaken the iron grip of custom. Not only have the traditions of society greatly changed in a relatively short span, but many of the specific rituals enabled by the elders may no longer be practiced or accessible. Additionally, the worship of ancestors in the traditional manner, (specifically the Kurgan-building peoples), may no longer be tenable.

Additionally, this aristocratic class can now observe the difference in between themselves and the subordinate population. For the steppe-populations in specific, this does not originate from genetics, (these populations would have been largely married-in), but rather from differences in lifestyles. The subordinate populations will be smaller and their bodies will be shaped by the labor that they perform. The aristocratic class will be shaped by their own lifestyle as well. Because they do not perform the same labor, instead training for warfare, their bodies will not be deformed in the same ways, likely to be more focused on muscle and endurance building. Aristocratic populations, on account of their pastoral lineage, also understand the practice of selective breeding, applying this principle onto themselves.

For the fourth point, I will quote Leo Strauss’ “The Origin of the Idea of Nature”:

“The original form of the doubt of authority, and therefore the direction which philosophy originally took or the perspective in which nature was discovered, was determined by the original character of authority. The assumption that there is a variety of divine codes leads to difficulties, since the various codes contradict one another. One code absolutely praises action which another absolutely condemns. One code demands the sacrifice of one’s first-born son, whereas another code forbids all human sacrifice as an abomination. The burial rites of one tribe provoke the horror of another. But what is decisive is the fact that the various codes contradict one another in what they suggest regarding the first things. The view that the gods were born from the earth cannot be reconciled with the view that the earth was made by the gods. Thus the question arises as to which code is the right code, and which account of the first things is the true account. The right way is now no longer guaranteed by authority; it becomes a question or the object of a quest. The primeval identification of the good with the ancestral is replaced by the fundamental distinction between the good and the ancestral: the quest for the right way or for the first things is the quest for the good as distinguished from the ancestral. It will probe to be the quest for what is good by nature as distinguished from what is good merely by convention.”

(I am unable to link this essay, as I accessed it through my work.)

These four characteristics enable the aristocratic class to begin the rationalization of nature, but do not directly cause it. The cause of the rationalization of nature is instead caused when the aristocratic class must defend itself from the rise of either democratic or monarchical forces, (monarchical forces typically coming from priestly classes).

Appeals to nature have been used throughout history by aristocrats to justify their status amongst the population. However, this claim is actually quite remarkable when we consider the fact that understanding the idea of nature as something separate from custom was a unique realization which originates with Greek thought. To quote Leo Strauss’ “The Origin of the Idea of Nature” once more:

“The idea of natural right must be unknown as long as the idea of nature is unknown. The discovery of nature is the work of philosophy. Where there is no philosophy, there is no natural right as such. The Old Testament, whose basic premise may be said to be the implicit rejection of philosophy, does not know “nature”: the Hebrew term for “nature” is unknown to the Hebrew Bible. It goes without saying that “heaven and earth”, for example, is not the same thing as “nature”. There is no knowledge of natural right as such in the Old Testament. The discovery of nature necessarily precedes the idea of natural right. Philosophy is older than political philosophy.”

Our conceptions of nature as something separate from custom, and therefore the entirety of the idea of natural right or law, originate with philosophy in ancient Greece, and were kept alive throughout antiquity. These concepts, in turn, served to justify the aristocratic orders which maintained the unique status of the West as a civilization directly juxtaposed to the much older status of the egalitarian rule of custom.

This idea of “nature vs. custom” should sound very similar to any educated reader. It is not very different from “nature vs. nurture” or even “nature vs. education”. This argument has been hashed out throughout the history of the West, but only because we are able to understand that the nature side of it exists at all. This argument, aside from its many non-political implications, can be reduced in the political sphere to the foundations of two bases of power: democratic and aristocratic. Of these, the argument which posits nature as the more important attribute is the aristocratic, which is perhaps alien to those of the Libertarian persuasion; the idea of human nature is what makes tyranny and aristocracy a horrifying prospect. However, as I have mentioned above, the concept of nature was utilized as a defense for aristocratic status and separation from the commons. In fact, the word “aristocracy” comes from the ancient Greek word “ἀριστοκρατίᾱ (aristokratíā)”, literally meaning “rule of the best”.

Donald Kagan’s “The Great Dialogue” has an excellent compilation of some quotes from opponents of democracy whom the reader will already be familiar with:

“This equality in all aspects of life, but particularly in political matters, was the target of the severest attacks by critics of democracy. Plato pointed out that democracy “distributes as sort of equality to the equal and unequal alike” (Republic, 558C). Aristotle said that to the democrat justice is “the enjoyment of arithmetical equality, and not the enjoyment of proportional equality based on merit” (Politics, 1317b). This is a basic complaint of the critics of democracy, and, of course, rests on the old conviction that somehow there are native distinctions among men which makes them differ in kind.”

In short, the idea of nature and specifically men’s plural natures are the foundational justifications for any aristocratic regime. In fact, a similar argument is still being made in modernity: Libertarians with more genetic concern justify free-market economics through the idea that it rewards intelligence. In antiquity, intelligence was not the only prioritized attribute, but spirit, or life force itself, were viewed as equally important, if not more so. For these reasons, aristocracy in antiquity was never based in a merchant class or on wealth, (although this has always mattered), but instead on martial traits and characteristics.

How aristocracy has shaped the political history of the West

The presence of a martial aristocracy shaped all of Western history until modernity. In antiquity the Greeks and Romans always had such a class: Athenian “democracy” was little more than the inclusion of the Hoplites in governance. In Rome, the Equites, (the term referring to both cavalry and a specific class), were a largely hereditary order. In Germania, kings and chieftains were accompanied by a comitatus, (companions), a warband not very dissimilar from the Kóryos, and both kingship and aristocratic status were tied to both male lineage and martial prowess.

Western culture has carried this martial tradition for the entirety of its pre-modern history. All the way from the time of the Greeks to the end of the Prussian aristocracy, a martial hierarchy either decided or had a huge impact the trajectory of the nations which make up “the West”.

All political power is rooted in violence. From the moment that custom ceased to be all-encompassing, the threat of force has been the deciding factor in all political decision-making. When aristocracies became landed, the land they were granted was directly tied to either martial rank or feats in battle. Even at the height of Christendom, lords and other nobles were expected to maintain retinues, (inspired by older Germanic tradition), and be ready to fight in the event of a war, (thus all those castles).

This is true even in so-called ‘democratic’ societies. As I have mentioned above, Athenian ‘democracy’ was in effect the enfranchisement of the Hoplite class, a small portion of the population who had to endure two years of military training and/or garrison duty before becoming citizens. Once these men were citizens, they were eligible to be called up for military service at any point. They also had to be native-born. The institution of Athenian democracy is not particularly unique for most of the classical world, many tribes or polis’ across antiquity had some form of representation for citizens, the unique attribute of Athenian ‘democracy’ is that it did away with most hierarchy above that of the citizen, whereas most other representative systems still gave privilege to its more aristocratic elements. It is also notable that Athenian ‘democracy’ lasted a shorter time than the American Republic has even if you add all of the interrupted periods together.

Some notion of citizenship has existed as long as martial societies have. It is impossible to completely keep those who are capable of organized violence, (and are often experienced in it), away from political power. This has generally resulted in two systems: one in which the army of the line received some kind of political power or representation and one in which the elite soldiers became nobles in their own right. Which of these two systems a society adopted largely depended on which kind of warfare it practiced; in times/areas in which mass armies of well-drilled troops were the standard practice, these troops tended to become some kind of ‘citizens’. In societies in which a small number of very elite soldiers did more of the fighting, these soldiers became a noble class of their own, (or at least served as noble retinues with their own privileges such as knights). At times these two systems overlayed one-another, such as in the Roman Republic.

In contrast, Eastern nations rarely maintained a professional warrior class. China, for example, conscripted most of its soldiers from the peasant class. When the Chinese did have professional soldiers, they often stationed them far from the imperial court and allowed them a great deal of freedom in the areas which they guarded.

Obviously such systems are not exclusive to the West. Japan is a notable example in which a warrior class maintained power in their own right. However, in Western antiquity, armies were made up of much larger numbers of ‘professionals’ or soldiers rather than exclusively warriors. This resulted in a distribution of political power that was much larger than in most areas of the world. This ‘power’, however, was not typically the power to make decisions, but rather to resist them. Despite notable brief exceptions in Athens, Rome and a few others, most states of this period were not giving representation per say to their warriors, but these warriors restricted the authority of those above them with the implicit threat of violence. They also restricted the influence of the masses with this same threat.

expands on this thought quite a bit in this essay, which I highly recommend.Closing thoughts:

When we pick up in chapter 3, we’ll be discussing the Christian period—starting with the Germanic conquests and ending in the Age of Absolutism. From there we’ll finally be moving into the topic at hand: the Enlightenment and the evolution into Progressivism as you and I know it, (likely two separate parts).

The reason I’m drawing this out in the way that I have been is to demonstrate exactly what the political and cultural climate in Europe, (and the world at large), was before the Enlightenment. A very surprising number of people greatly misunderstand what the picture really looked like at the time that Enlightenment philosophers and authors were writing, and it is imperative that this is properly drawn out in order to understand exactly what the Enlightenment and its subsequent revolutions really were. Understanding the Enlightenment is, of course, crucial to understanding Progressivism and Liberalism generally.

Thank you all for reading this chapter. I’m sorry that it took so long, but it involved a substantial amount of research to ensure that my memory was not misconstruing any facts. Future parts are much more fresh on my mind and allow me to use primary sources more, so expect a faster pace going forward.