On the Origins of Progressivism 3

Early Christianity and its Relationship to Aristocracy and Philosophy

Prior issues in this series:

Brief Disclaimer

Thus far in this series I have maintained a distanced perspective on the phenomena discussed within. While I would like to do so throughout these writings, current events have made this essay controversial. While I have already delayed the essay around two weeks past when it was mostly complete, the “debate” within the online sphere has remained: is Christianity to the detriment of the West? This debate has largely consisted of individuals with preexisting biases talking past one-another and was pretty much useless, but I did not want to be thought contributing to it with this piece.

This essay was drafted months before the most recent iterations of that debate, and has nothing to do with any current events. The goal of this piece is to take a sober look at the effects of early Christianity, not to make an analysis of its modern variant (which is quite different in a number of ways).

In addition, while parts of this essay will be quite ‘critical,’ (to the extent that a true telling of history can be deemed ‘critical’) this is only for the purpose of carrying this series to its intended conclusion. Were I writing a different series, I would cover different aspects of this religion.

No religion or social system is without flaw: this is a human universal. Saying this is not to criticize a religion or social system itself, but rather to point out that human corruption carries any tendency forward.

Without further delay…

Christianity

How Christianity is Introduced to and Spreads Within Rome

“Since therefore the most sublime efforts of philosophy can extend no further than feebly to point out the desire, the hope, or, at most, the probability, of a future state, there is nothing, except a divine revelation, that can ascertain the existence and describe the condition, of the invisible country which is destined to receive the souls of men after their separation from the body. But we may perceive several defects inherent to the popular religions of Greece and Rome, which rendered them very unequal to so arduous a task. 1. The general system of their mythology was unsupported by any solid proofs; and the wisest among the Pagans had already disclaimed its usurped authority. 2. The description of the infernal regions had been abandoned to the fancy of painters and of poets, who peopled them with so many phantoms and monsters, who dispensed their rewards and punishments with so little equity, that a solemn truth, the most congenial to the human heart, was oppressed and disgraced by the absurd mixture of the wildest fictions. 3. The doctrine of a future state was scarcely considered among the devout polytheists of Greece and Rome as a fundamental article of faith. The providence of the gods, as it related to public communities rather than to private individuals, was principally displayed on the visible theatre of the present world. The petitions which were offered on the altars of Jupiter or Apollo expressed the anxiety of their worshippers for temporal happiness, and their ignorance or indifference concerning a future life. The important truth of the immortality of the soul was inculcated with more diligence, as well as success, in India, in Assyria, in Egypt, and in Gaul; and since we cannot attribute such a difference to the superior knowledge of the barbarians, we must ascribe it to the influence of an established priesthood, which employed the motives of virtue as the instrument of ambition.”

-Edward Gibbon, “The History of the Fall of the Roman Empire” (Chapter XV)

While we will be discussing the physical manner in which Christianity spread, (and amongst whom), it is first important to understand why it succeeded where other religions of the time failed. One major issue is that many philosophers and their followers were relatively agnostic, with some even being atheists in the modern sense of the term, meaning that significant portions of the cultural elite were unconcerned with investigating the afterlife specified by Roman state religion. Additionally, the afterlife for the common man, (when specified at all), was often quite dreary, particularly in older sources such as Homer. This is particularly important to consider as commoners in Rome would be much more familiar with the works of Homer, Virgil and other poets than he would be Plato or other philosophers who put forth alternative ideas of the afterlife.

Now, Gibbon does not delve into the various mystery cults and such which were popular throughout the empire at this time, (partially because knowledge of these was more scarce at the time of his writing). These cults often had their own visions of the afterlife. However, many of these excluded slaves and lower classes. Mithraism, for example, was almost exclusive to those related to military service. However, where these cults did allow slaves or lower classes to participate these individuals often participated heavily, but these were often smaller localized affairs. Due to the nature of these cults, they often had other exclusive aspects, (such as primarily focusing on women), which limited their appeal as an individual religion. These cults also often involved the larger Roman civic religion to some extent, rather than outright contradicting it.

Various schools of philosophy did contain visions of an afterlife which differed from the state religion. Platonism, (and Neoplatonism), in particular drastically differed from the underworld described by Homer. However, as stated above, these ideas circulated primarily in elite circles, rather than amongst the commoners.

(I would like to note here that I am aware that Gibbon is a somewhat controversial source. Often he can be blatantly biased on the subject of early Christianity. However, when I use him I will be reinforcing his claims with embedded hyperlinks as I have above, not simply relying on his word. The linked source for his book also confronts inaccuracies which he may have been unaware of when writing.)

Many readers will be quick to point out the power of Martyrdom as a demonstration of the faith of Christians, something which could have assisted in the conversion of pagans. I don’t want to downplay this; I’m sure that Martyrdom did serve this purpose, but there are other aspects more relevant to the thesis of this series which I would like to focus on.

The supernatural gifts, which even in this life were ascribed to the Christians above the rest of mankind, must have conduced to their own comfort, and very frequently to the conviction of infidels. Besides the occasional prodigies, which might sometimes be effected by the immediate interposition of the Deity when he suspended the laws of Nature for the service of religion, the Christian church, from the time of the apostles and their first disciples [Chapter 6], has claimed an uninterrupted succession of miraculous powers, the gift of tongues, of vision, and of prophecy, the power of expelling dæmons, of healing the sick, and of raising the dead. The knowledge of foreign languages was frequently communicated to the contemporaries of Irenæus, though Irenæus himself was left to struggle with the difficulties of a barbarous dialect, whilst he preached the gospel to the natives of Gaul. The divine inspiration, whether it was conveyed in the form of a waking or of a sleeping vision, is described as a favor very liberally bestowed on all ranks of the faithful, on women as on elders, on boys as well as upon bishops [Chapter 9]. When their devout minds were sufficiently prepared by a course of prayer, of fasting, and of vigils, to receive the extraordinary impulse, they were transported out of their senses, and delivered in ecstasy what was inspired, being mere organs of the Holy Spirit, just as a pipe or flute is of him who blows into it. We may add, that the design of these visions was, for the most part, either to disclose the future history, or to guide the present administration, of the church. The expulsion of the dæmons from the bodies of those unhappy persons whom they had been permitted to torment, was considered as a signal though ordinary triumph of religion, and is repeatedly alleged by the ancient apologists, as the most convincing evidence of the truth of Christianity. The awful ceremony was usually performed in a public manner [Chapter 23], and in the presence of a great number of spectators; the patient was relieved by the power or skill of the exorcist, and the vanquished dæmon was heard to confess that he was one of the fabled gods of antiquity, who had impiously usurped the adoration of mankind. But the miraculous cure of diseases of the most inveterate or even preternatural kind can no longer occasion any surprise, when we recollect, that in the days of Irenæus, about the end of the second century, the resurrection of the dead was very far from being esteemed an uncommon event [Paragraph 4]; that the miracle was frequently performed on necessary occasions, by great fasting and the joint supplication of the church of the place, and that the persons thus restored to their prayers had lived afterwards among them many years. At such a period, when faith could boast of so many wonderful victories over death, it seems difficult to account for the scepticism of those philosophers, who still rejected and derided the doctrine of the resurrection. A noble Grecian had rested on this important ground the whole controversy, and promised Theophilus, Bishop of Antioch, that if he could be gratified with the sight of a single person who had been actually raised from the dead, he would immediately embrace the Christian religion. It is somewhat remarkable, that the prelate of the first eastern church, however anxious for the conversion of his friend, thought proper to decline this fair and reasonable challenge.

The miracles of the primitive church, after obtaining the sanction of ages, have been lately attacked in a very free and ingenious inquiry, which, though it has met with the most favorable reception from the public, appears to have excited a general scandal among the divines of our own as well as of the other Protestant churches of Europe. Our different sentiments on this subject will be much less influenced by any particular arguments, than by our habits of study and reflection; and, above all, by the degree of evidence which we have accustomed ourselves to require for the proof of a miraculous event. The duty of an historian does not call upon him to interpose his private judgment in this nice and important controversy; but he ought not to dissemble the difficulty of adopting such a theory as may reconcile the interest of religion with that of reason, of making a proper application of that theory, and of defining with precision the limits of that happy period, exempt from error and from deceit, to which we might be disposed to extend the gift of supernatural powers. From the first of the fathers to the last of the popes, a succession of bishops, of saints, of martyrs, and of miracles, is continued without interruption; and the progress of superstition was so gradual, and almost imperceptible, that we know not in what particular link we should break the chain of tradition. Every age bears testimony to the wonderful events by which it was distinguished, and its testimony appears no less weighty and respectable than that of the preceding generation, till we are insensibly led on to accuse our own inconsistency, if in the eighth or in the twelfth century we deny to the venerable Bede, or to the holy Bernard, the same degree of confidence which, in the second century, we had so liberally granted to Justin or to Irenæus. If the truth of any of those miracles is appreciated by their apparent use and propriety, every age had unbelievers to convince, heretics to confute, and idolatrous nations to convert; and sufficient motives might always be produced to justify the interposition of Heaven. And yet, since every friend to revelation is persuaded of the reality, and every reasonable man is convinced of the cessation, of miraculous powers, it is evident that there must have been some period in which they were either suddenly or gradually withdrawn from the Christian church. Whatever æra is chosen for that purpose, the death of the apostles, the conversion of the Roman empire, or the extinction of the Arian heresy, the insensibility of the Christians who lived at that time will equally afford a just matter of surprise. They still supported their pretensions after they had lost their power. Credulity performed the office of faith; fanaticism was permitted to assume the language of inspiration, and the effects of accident or contrivance were ascribed to supernatural causes. The recent experience of genuine miracles should have instructed the Christian world in the ways of Providence, and habituated their eye (if we may use a very inadequate expression) to the style of the divine artist. Should the most skilful painter of modern Italy presume to decorate his feeble imitations with the name of Raphæl or of Correggio, the insolent fraud would be soon discovered, and indignantly rejected.

Whatever opinion may be entertained of the miracles of the primitive church since the time of the apostles, this unresisting softness of temper, so conspicuous among the believers of the second and third centuries, proved of some accidental benefit to the cause of truth and religion. In modern times, a latent and even involuntary scepticism adheres to the most pious dispositions. Their admission of supernatural truths is much less an active consent than a cold and passive acquiescence. Accustomed long since to observe and to respect the invariable order of Nature, our reason, or at least our imagination, is not sufficiently prepared to sustain the visible action of the Deity.

But, in the first ages of Christianity, the situation of mankind was extremely different. The most curious, or the most credulous, among the Pagans, were often persuaded to enter into a society which asserted an actual claim of miraculous powers. The primitive Christians perpetually trod on mystic ground, and their minds were exercised by the habits of believing the most extraordinary events. They felt, or they fancied, that on every side they were incessantly assaulted by dæmons, comforted by visions, instructed by prophecy, and surprisingly delivered from danger, sickness, and from death itself, by the supplications of the church. The real or imaginary prodigies, of which they so frequently conceived themselves to be the objects, the instruments, or the spectators, very happily disposed them to adopt with the same ease, but with far greater justice, the authentic wonders of the evangelic history; and thus miracles that exceeded not the measure of their own experience, inspired them with the most lively assurance of mysteries which were acknowledged to surpass the limits of their understanding. It is this deep impression of supernatural truths which has been so much celebrated under the name of faith; a state of mind described as the surest pledge of the divine favor and of future felicity, and recommended as the first, or perhaps the only merit of a Christian. According to the more rigid doctors, the moral virtues, which may be equally practised by infidels, are destitute of any value or efficacy in the work of our justification.

This is quite a controversial passage, so I’ll clarify some points.

Firstly, it must be noted that early Christianity existed in a world in which the sorts of miraculous events written about by Church Fathers were also viewed as commonplace, (albeit different), in all religious circles. Pagans commonly used magic spells, and ‘seers’ were not uncommon. Oracles were still in heavy use during this time period.

In other words, what is being asserted about early Christianity is not unique to that religion, but rather a part of the religious landscape of antiquity. As such, this passage should not be taken as criticism of that religion in particular, but rather as demonstrative of the world in which Christianity arose. It would have been the understanding of the common man that this new religion was presenting a direct link with an all-seeing God in a similar way to what can be observed in many African or Latin American sects today, rather than the manner in which Western Christians understand their religion.

The issues with all of this should be apparent, and if they are not then one can simply look at the various heresies which splintered from the early Church. While the Jewish religion also left room for the direct intervention of God in human affairs, it did so underneath a robust and hierarchical system of Priests, (later Rabbis). Early Christianity did not have such a structure, particularly at the mid-level. This means that early proselytization, ritual and even teachings of the gospel were prone to be misconstrued.

These first few centuries of Christianity were the most crucial in terms of its later direction and civic relationship. While the later Church was responsible for the codification of mainline Christianity, (excommunicating all others), much of the trajectory of Christianity was decided during this Subapostolic era.

For our purposes, this is important for two reasons: early Christianity’s relationship with philosophy, and its relationship with aristocracy. But first, a brief summary of how Christianity rises from its status as a small sect of the Jewish faith to the majority religion of Rome.

How Christianity Becomes Hegemon

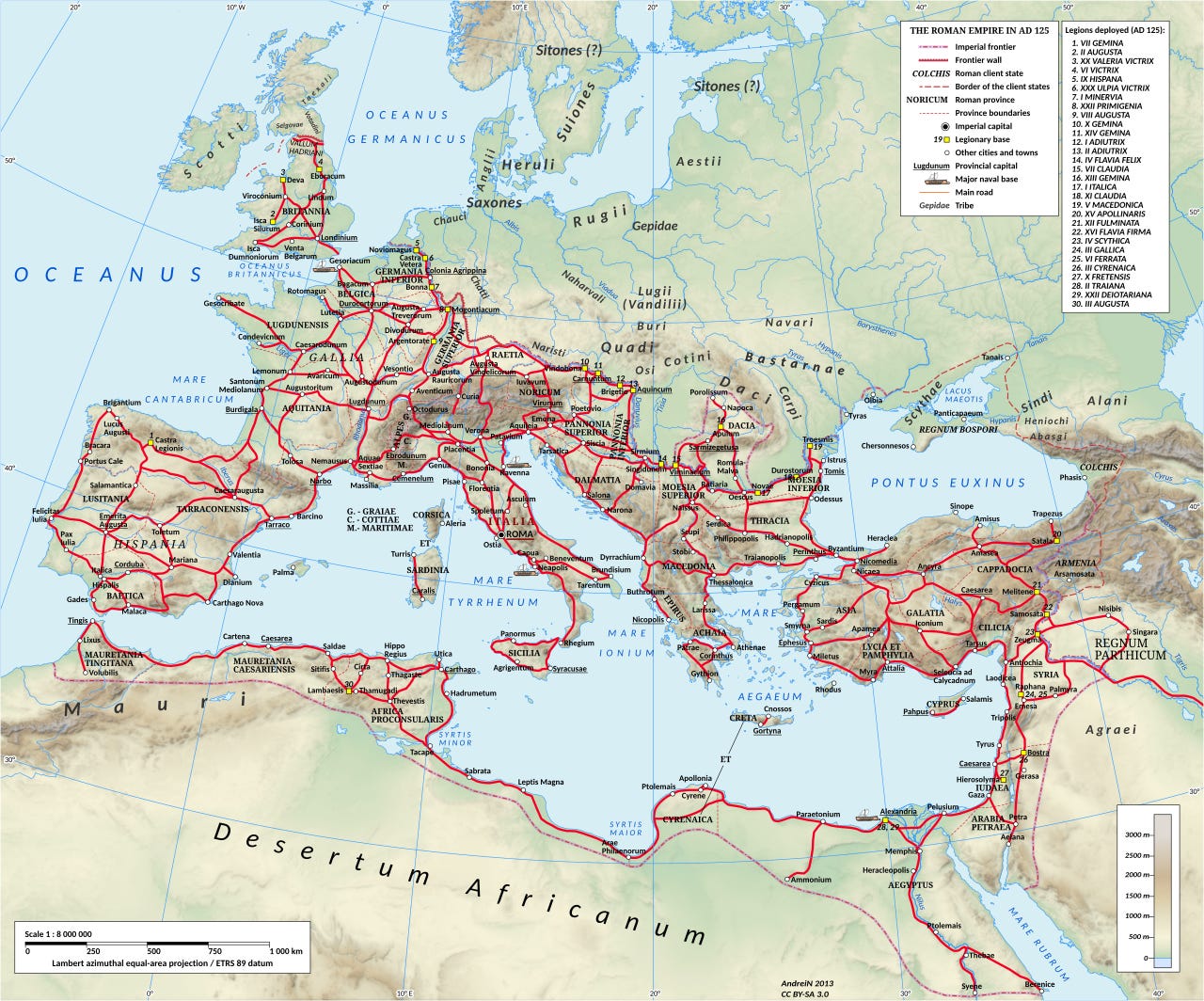

In terms of logistics, Christianity was able to spread rapidly due to the safety ensured by the Roman military, (Pax Romana), as well as the infrastructure system of the empire. Additionally, the Roman people by and large spoke Latin, and in the Eastern provinces also often spoke Greek. The events of Jesus’ life are often in coastal areas of the province of Judea, meaning that many early converts were seafarers in some capacity.

Christianity from the beginning advocated proselytization, which took the form not only of what we would now call missionaries, but also of charity. Christian churches provided charitable resources to the urban poor in a way which Roman institutions often failed to do. The religion originated in a time of debt crisis within Judea, which exacerbated the situation of the lower classes to a degree which increased the effectiveness of this tactic.

As we have discussed, Roman state religion often painted an incoherent picture of the afterlife, and earlier figures painted a very bleary one for the common man. The various mystery cults of the time were often uninclusive and limited in their own ideas of an afterlife. Christianity, in contrast, not only holds a view of an afterlife which is very much inclusive to the lower classes, but in fact seems to favor them in terms of their likelihood of attaining salvation.

In addition, the early Christian worldview is in stark contrast to that which existed in that it did not denigrate commoners. The Roman worldview which upheld nobility as something sacred, (or sacred-adjacent), implicitly viewed commoners, (not to mention slaves), as beneath aristocrats in value and role. Naturally, a worldview which does essentially the reverse appeals to these underclasses.

As such, Christianity spreads rapidly, (though by no means exclusively), among the lower classes. The huge numbers of urban poor, land-bound tenants and slaves are by and large the first Christians of the empire. Many have emphasized that it spread quickly among women as well, but I could find no particular evidence of this; from my research it seems as though this was a perception which outsiders held due to shared worship and the existence of Deaconesses. It is more likely that women of any particular class shared the worship practices of their husbands or others within the same social strata.

One key reason why slaves may have taken up the religion with such speed is that Roman slaves were often separated from their ethnic religious practices and denigrated by Roman ones. Christianity, as a universal religion, allowed them to practice a faith which was not that of their masters, one which viewed them as spiritual equals and one which promised them a different and better life after their current one.

Christianity remained a minority religion for several centuries, but persecution waned over time. Part of the reason that this may have been that Christianity began to spread upwards in class over time. The writings of the Church Fathers which I will reference extensively are largely designed for an educated and elite audience, perhaps trying to court them through the use of arguments related to Greek philosophy. It seems that by the third century Christianity was no longer a religion only for the poor, but also included elites in its ranks, (although in much smaller numbers).

Constantine’s conversion, (although there were pagan emperors and was even persecution after him), is the final push to make this new religion dominant. The possible reasons for his use of Christianity and its symbols include legitimate conversion, a large number of Christians in his army and an effort to sway the population of Rome to supporting him. There is not much evidence of Christian overrepresentation in his army, so leaving aside the idea that he legitimately saw a cross in the night, the last is the most likely. When Constantine claimed to see the vision of the cross in the night sky, it was during a civil war with Maxentius, an emperor who had retained his position through a series of ‘populist’ measures. Perhaps the invocation of Christian symbology was designed to sway some of his more hastily assembled troops to Constantine’s side, or to ingratiate him with the population of Rome after the battle.

Whatever the reason, he retained his conversion until his death, and significantly favored Christians throughout his reign. While later emperors would try to reverse his effect, Christianity had become the dominant religion of Rome and would never again fall from this status.

Now, we will be returning to the time before Constantine, to explore the differences between the pre-Christian and Christian worldviews.

Early Christianity and Philosophy

Christianity’s relationship with philosophy is and was complex. For starters, almost all philosophy from antiquity relates to Christianity in an antagonistic or semi-antagonistic manner. As I have explained in the previous iteration, philosophy in antiquity was understood as and largely was an anti-egalitarian force.

While Alfred North Whitehead states that the Western Canon “consists of a series of footnotes to Plato”, he is referring to its post-Christian state. In Antiquity, there were rival schools which conflicted with Plato and the Platonic schools. There were some who believed that the classical-era philosophers represented a corruption and preferred to glimpse back further, interpreting the works of Homer and Pindar as a sort of philosophy. Still others practiced schools which were inspired from others in the classic-era but antithetical to Platonism, such as Epicureanism or Stoicism. These various schools of thought were very different from one-another and certainly different from the Christian teachings. Aristotle taught that humility was something of a vice, although this was not his view alone. Plato would become more hegemonic later largely as a result of actions taken by the Church.

While the Platonic schools aligned with Christianity in a number of ways, their doctrine, (Neoplatonism in particular), was explicitly focused on a sort of ‘enlightenment’ only really achievable by a small philosophical elite. Enlightenment, (or salvation as we’ll call it), was an intellectual achievement done by way of reason; much in contrast to the Christian salvation stemming from faith.

In addition, philosophy was still known as a tyrannical element amongst Romans, just as it had been amongst the Greeks. Most philosophers were hostile to the ‘demos’ and democracy in general, and many schools held the Plebians and slaves in contempt. This obviously contrasts with Christianity in regards to its humanizing of these classes, but also places philosophy in contention with early Christians themselves, who were often of these classes themselves.

To further demonstrate this point, allow me to bring in a few quotes directly from the bible which are representative of the general Christian attitude towards philosophy:

Colossians 2:8: “See to it that no one takes you captive through philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the world, and not according to Christ.”

1 Corinthians 1:20–23: “Where is the wise person? Where is the teacher of the law? Where is the philosopher of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world? … Jews demand signs and Greeks look for wisdom, but we preach Christ crucified: a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles.”

1 Corinthians 2:4–5: “My message and my preaching were not with wise and persuasive words, but with a demonstration of the Spirit’s power, so that your faith might not rest on human wisdom, but on God’s power.”

1 Corinthians 3:18–20: “Do not deceive yourselves. If any of you think you are wise by the standards of this age, you should become ‘fools’ so that you may become wise. For the wisdom of this world is foolishness in God’s sight.”

1 Timothy 6:20–21: “Avoid the irreverent babble and contradictions of what is falsely called knowledge (gnosis), for by professing it some have swerved from the faith.”

Matthew 22:37: And he said to him, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.”

These verses are obviously taken aside from their broader context, but certainly don’t demonstrate a ‘friendly’ relationship between the Christian worldview and philosophy. Now, these verses are predominantly concerned with areas in which philosophy and Christianity conflict, but given that philosophy is concerned with investigating the nature of things, this is far from uncommon. When we combine this with areas in which philosophy contradicts not only with faith, but also with the commonly held Christian system of morality, (to include its political implications), we will see that this is quite common.

On the other hand, aspects of Christian thought are clearly informed by the various philosophers of antiquity. The urban centers near where Jesus of Nazareth was born and raised was highly hellenized, (Jesus is a hellenized version of the name Yeshua, or Joshua), meaning that the people of the region were likely influenced by Greek ideas. While the early Church spoke against philosophy often, links between Plato, Neoplatonism and Christian thought abound. Additionally, in the subapostolic era, many Christians would use Stoic arguments to reinforce the case for God and Christian theology.

It would not be difficult to argue that Christianity’s impact is largely the conversion of Platonic ideas into a universalist religion. However, as this religion became one of the masses, it lost many of the specific ideas expressed in Platonic philosophy and retained only a value system which had some resemblance.

While some Christian theologians engaged in what they called “philosophy”, it is important here to draw a distinction. Philosophy, by its nature, cannot be rooted in a single worldview limited by a holy text, but must be willing to engage with investigation outside of one tradition. This is not to say that conclusions cannot be drawn from philosophic investigation which align or confirm a specific faith or tradition, but rather that the investigation cannot begin with a single tradition. Early theologians were not doing this, but instead were taking insights from philosophy and using it as reinforcement for theology, choosing specific arguments from Plato and later some Stoic scholars as evidence of the truth of their tradition. Such actions can hardly be called philosophy, but rather should be viewed as theology. Some quotes which confirm that this was, indeed, the perspective of the Church Fathers are listed below:

Clement of Alexandria, Stromateis, Book 1 Chapter 5: “Philosophy, therefore, was a preparation, paving the way for him who is perfected in Christ.” (This entire chapter as well as Chapter 3 and 19 also reinforce this notion.)

Clement of Alexandria, Stromateis, Book 1 Chapter 19: “Whether, then, they say that the Greeks gave forth some utterances of the true philosophy by accident, it is the accident of a divine administration (for no one will, for the sake of the present argument with us, deify chance); or by good fortune, good fortune is not unforeseen.”

Justin Martyr, Second Apology, Chapter 13: “Whatever things were rightly said among all men, are the property of us Christians.”

Tertullian, On the Prescription of Heretics, Chapter 7: “Whence spring those "fables and endless genealogies," and "unprofitable questions," and "words which spread like a cancer? " From all these, when the apostle [Paul] would restrain us, he expressly names philosophy as that which he would have us be on our guard against. Writing to the Colossians, he says, "See that no one beguile you through philosophy and vain deceit, after the tradition of men, and contrary to the wisdom of the Holy Ghost." He had been at Athens, and had in his interviews (with its philosophers) become acquainted with that human wisdom which pretends to know the truth, whilst it only corrupts it, and is itself divided into its own manifold heresies, by the variety of its mutually repugnant sects. What indeed has Athens to do with Jerusalem? What concord is there between the Academy and the Church? what between heretics and Christians? Our instruction comes from "the porch of Solomon," who had himself taught that "the Lord should be sought in simplicity of heart." Away with all attempts to produce a mottled Christianity of Stoic, Platonic, and dialectic composition! We want no curious disputation after possessing Christ Jesus, no inquisition after enjoying the gospel! With our faith, we desire no further belief.”

Also worth reading from Justin is the Dialogue with Trypho, which is concerned primarily with speaking on which philosophies are tolerable to the Christian. This dialogue is so concerned with the limits of philosophy as to suggest that if all philosophy were informed by Godly men, there would be no disagreement between philosophers at all, and therefore all wisdom is to be taken from “prophets”, (better understood as Apostles).

Two centuries later, Augustine had a slightly friendlier attitude:

Augustine, Retractions, Book 1 Chapter 13: “This very thing, which is now called the Christian religion, existed among the ancients, nor was it lacking from the beginning of the human race until Christ Himself came in the flesh, whence the true religion, that already existed, began to be called Christian.”

However, it is worth noting that, (within the broader context), this quote implies that a specific subset of philosophy was close to correct, (given earlier Church Father’s works we can assume this was a subset of the Platonic), which limits tolerated philosophy to that which lined up with the Christian worldview anyways.

In other words, early Christians are often diametrically opposed to the idea of philosophy. When they do use the term “philosophy” in a positive light, they refer only to a very small subset of the Platonic which was deemed to have been divinely inspired.

Lastly, Constantine funded a great deal of “Scriptoria”, copying workshops designed for the maintenance of Church writings and the Bible. These would become the primary maintence mechanism for much of the written work from not only this era, but also antiquity. The explicit Christian nature of these organizations meant that their primary focus was, of course, on Christian works. These scribes were often forbidden from maintaining certain pieces of literature from non-Christian sources. In addition, later emperors and Bishops from both the Eastern and Western empires ordered the destruction of anti-Christian literature, sometimes including pieces which were pre-Christian but had contradictory worldviews. At times, pieces were even edited to fit within the correct moral framework. I don’t want to overemphasize this point: neglect due to lack of interest is hardly the same as outright censorship, but the fact that there was such a lack of interest in pieces such as Aristotle’s “On Philosophy” oncemore demonstrate a relationship which was at best disinterested.

Early Christianity and Aristocracy

As we discussed in the last chapter, philosophy is rooted in the idea of nature, which is an intellectual defense for aristocratic hierarchy. Early Christianity was generally opposed to philosophy with small exceptions for the more theological considerations of some Platonists. However, this on its own cannot be taken to imply that early Christians were opposed to aristocracy itself, meaning that this must be investigated separately.

Early Christians were certainly often opposed to wealth inequality. A great deal of the second portion of the book of Acts is dedicated to demonstrating how the Apostles and their followers shared possessions in common and avoided inequality. This was often reinforced by early Church Fathers, who often advocated the emulation of these communities. Additionally, Christian charity was largely concerned with the assistance for and uplifting of the poor. This, of course, is much less radical, demonstrating a shift within the first few centuries of the religion. For some examples from Acts:

Acts 2:44–45: “All who believed were together and had all things in common; they sold their possessions and goods and distributed them to all, as any had need.”

Acts 4:32–35: “No one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common… There was not a needy person among them.”

Simple material wealth, however, is more of a symptom of aristocracy than its definition, as we explored in the last chapter. As such, we must now investigate Christianity’s relationship with aristocratic hierarchy as a social institution. (If you are interested in the subject of early Christianity and wealth inequality, I read bits of Roman Montero’s book “All Things in Common” in researching this, but found it to be a bit off topic for this essay.)

Whereas Aristotle argued that some men were natural-born slaves, Christianity typically finds itself arguing that men are equal in value, if different in traits. This worldview is contradictory to a world in which one’s worth was intrinsically tied to their bloodline, which was the view held, (at least in elite circles), for most of antiquity.

This being said, nothing within the Bible, (that I have found in my research at least), explicitly argues that men do not have differing natures, and in fact there are several verses which could be used to argue that they do. However, interpreting the Bible in a way which is friendly towards the idea of aristocracy was not something which early practitioners were motivated to do. In fact, due to Christianity’s early spread amongst the lower classes, they had good incentive to do quite the opposite. Christianity’s advocacy of spiritual equality before God is very easily taken for equality in this Earth if one reads with such an anti-hierarchical bias. This is easily evidenced in our own time among some more liberal interpretations of the religion.

To finally get into the weeds of it, the early Christian worldview is nothing short of hostile towards the aristocratic worldview outlined in the last piece. It explicitly rejects the sorts of virtues which this order held in respect, replacing them with a completely different moral system. These two worldviews were completely in opposition.

1 Corinthians 1:26-29: “For consider your calling, brothers and sisters: not many of you were wise by human standards; not many were powerful; not many were of noble birth. But God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong. God chose the lowly and despised things of the world—and the things that are not—to nullify the things that are, so that no one may boast before him.”

Matthew 20:20-28: “Jesus called them together and said, “You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be your slave—just as the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.” (This story is repeated in Mark and Luke, but the Mark version is mostly identical.)

The Luke version, (22:24-27): “Jesus said to them, “The kings of the Gentiles lord it over them; and those who exercise authority over them call themselves Benefactors. But you are not to be like that. Instead, the greatest among you should be like the youngest, and the one who rules like the one who serves. For who is greater, the one who is at the table or the one who serves? Is it not the one who is at the table? But I am among you as one who serves.”

This sentiment is not limited to only the Bible itself.

Clement of Alexandria, Exhortation to the Heathen, Chapter 12: “It is time, then, for us to say that the pious Christian alone is rich and wise, and of noble birth, and thus call and believe him to be God’s image, and also His likeness, having become righteous and holy and wise by Jesus Christ, and so far already like God. Accordingly this grace is indicated by the prophet, when he says, “I said that ye are gods, and all sons of the Highest.” For us, yea us, He has adopted, and wishes to be called the Father of us alone, not of the unbelieving. Such is then our position who are the attendants of Christ.”

Clement of Alexandria, Stromateis, Book 2 Chapter 4: “Plato the philosopher, also, in The Laws, says, “that he who would be blessed and happy, must be straight from the beginning a partaker of the truth, so as to live true for as long a period as possible; for he is a man of faith. But the unbeliever is one to whom voluntary falsehood is agreeable; and the man to whom involuntary falsehood is agreeable is senseless; neither of which is desirable. For he who is devoid of friendliness, is faithless and ignorant.” And does he not enigmatically say in Euthydemus, that this is “the regal wisdom”? In The Statesman he says expressly, “So that the knowledge of the true king is kingly; and he who possesses it, whether a prince or private person, shall by all means, in consequence of this act, be rightly styled royal.” Now those who have believed in Christ both are and are called Chrestoi (good), as those who are cared for by the true king are kingly. For as the wise are wise by their wisdom, and those observant of law are so by the law; so also those who belong to Christ the King are kings, and those that are Christ’s Christians. Then, in continuation, he adds clearly, “What is right will turn out to be lawful, law being in its nature right reason, and not found in writings or elsewhere.” And the stranger of Elea pronounces the kingly and statesmanlike man “a living law.” Such is he who fulfils the law, “doing the will of the Father,” inscribed on a lofty pillar, and set as an example of divine virtue to all who possess the power of seeing. The Greeks are acquainted with the staves of the Ephori at Lacedæmon, inscribed with the law on wood. But my law, as was said above, is both royal and living; and it is right reason. “Law, which is king of all—of mortals and immortals,” as the Bœotian Pindar sings. For Speusippus, in the first book against Cleophon, seems to write like Plato on this wise: “For if royalty be a good thing, and the wise man the only king and ruler, the law, which is right reason, is good;” which is the case. The Stoics teach what is in conformity with this, assigning kinghood, priesthood, prophecy, legislation, riches, true beauty, noble birth, freedom, to the wise man alone. But that he is exceedingly difficult to find, is confessed even by them.”

The following quote is very long, but is perhaps the most representative summary of how early Christians viewed the martial aristocracies central to antiquity.

Lactantius, Divine Institutes, Book 5 Chapter 6: “And the source of all these evils was lust; which, indeed, burst forth from the contempt of true majesty. For not only did they who had a superfluity fail to bestow a share upon others, but they even seized the property of others, drawing everything to their private gain; and the things which formerly even individuals laboured to obtain for the common use of men, were now conveyed to the houses of a few. For, that they might subdue others by slavery, they began especially to withdraw and collect together the necessaries of life, and to keep them firmly shut up, that they might make the bounties of heaven their own; not on account of kindness, a feeling which had no existence in them, but that they might sweep together all the instruments of lust and avarice. They also, under the name of justice, passed most unequal and unjust laws, by which they might defend their plunder and avarice against the force of the multitude. They prevailed, therefore, as much by authority as by strength, or resources, or malice. And since there was in them no trace of justice, the offices of which are humanity, equity, pity, they now began to rejoice in a proud and swollen inequality, and made themselves higher than other men, by a retinue of attendants, and by the sword, and by the brilliancy of their garments. For this reason they invented for themselves honours, and purple robes, and fasces, that, being supported by the terror produced by axes and swords, they might, as it were by the right of masters, rule them, stricken with fear, and alarmed. Such was the condition in which the life of man was placed by that king who, having defeated and put to flight a parent, did not seize his kingdom, but set up an impious tyranny by violence and armed men, and took away that golden age of justice, and compelled men to become wicked and impious, even from this very circumstance, that he turned them away from God to the worship of himself; and the terror of his excessive power had extorted this.”

“For who would not fear him who was girded about with arms, whom the unwonted gleam of steel and swords surrounded? Or what stranger would he spare who had not even spared his own father? Whom, in truth, should he fear, who had conquered in war, and destroyed by massacre the race of the Titans, which was strong and excelling in might? What wonder if the whole multitude, pressed by unusual fear, had given themselves up to the adulation of a single man? Him they venerated, to him they paid the greatest honour. And since it is judged to be a kind of obsequiousness to imitate the customs and vices of a king, all men laid aside piety, lest, if they should live piously, they might seem to upbraid the wickedness of the king. Thus, being corrupted by continual imitation, they abandoned divine right, and the practice of living wickedly by degrees became a habit. And now nothing remained of the pious and excellent condition of the preceding age; but justice being banished, and drawing with her the truth, left to men error, ignorance, and blindness. The poets therefore were ignorant, who sung that she fled to heaven, to the kingdom of Jupiter. For if justice was on the earth in the age which they call golden, it is plain that she was driven away by Jupiter, who changed the golden age. But the change of the age and the expulsion of justice is to be deemed nothing else, as I have said, than the laying aside of divine religion, which alone effects that man should esteem man dear, and should know that he is bound to him by the tie of brotherhood, since God is alike a Father to all, so as to share the bounties of the common God and Father with those who do not possess them; to injure no one, to oppress no one, not to close his door against a stranger, nor his ear against a suppliant, but to be bountiful, beneficent, and liberal, which Tullius thought to be praises suitable to a king. This truly is justice, and this is the golden age, which was first corrupted when Jupiter reigned, and shortly afterwards, when he himself and all his offspring were consecrated as gods, and the worship of many deities undertaken, had been altogether taken away.”

It is notable that the work quoted above is directly addressed to Emperor Constantine by an author who would later become an advisor to the emperor and tutor to his son.

I would lastly like to add that several of the early Church Fathers were outright pacifists, (or at least held strong sympathies in such a direction), which is not only part of their opposition to martial aristocracy, but also an interesting footnote:

Athenagoras, A Plea for Christians, Chapter 35: “For when they know that we cannot endure even to see a man put to death, though justly”

Justin Martyr, First Apology, Book 1 Chapter 39: “For from Jerusalem there went out into the world, men, twelve in number, and these illiterate, of no ability in speaking: but by the power of God they proclaimed to every race of men that they were sent by Christ to teach to all the word of God; and we who formerly used to murder one another do not only now refrain from making war upon our enemies, but also, that we may not lie nor deceive our examiners, willingly die confessing Christ. For that saying, The tongue has sworn but the mind is unsworn, might be imitated by us in this matter. But if the soldiers enrolled by you, and who have taken the military oath, prefer their allegiance to their own life, and parents, and country, and all kindred, though you can offer them nothing incorruptible, it were verily ridiculous if we, who earnestly long for incorruption, should not endure all things, in order to obtain what we desire from Him who is able to grant it.”

While Justin grants soldiers of the empire specifically the ability to obey their legal duties for their time of enlistment, Hippolytus is much less lenient:

Hippolytus, Apostilic Tradition, Chapter 16:“A soldier of the civil authority must be taught not to kill men and to refuse to do so if he is commanded, and to refuse to take an oath; if he is unwilling to comply, he must be rejected. A military commander or civic magistrate that wears the purple must resign or be rejected. If a catechumen or a believer seeks to become a soldier, they must be rejected, for they have despised God.”

Lastly, Tertullian is very explicit in his forbidding of military service:

Tertullian, De Corona, Chapter 11: “To begin with the real ground of the military crown, I think we must first inquire whether warfare is proper at all for Christians. What sense is there in discussing the merely accidental, when that on which it rests is to be condemned? Do we believe it lawful for a human oath to be superadded to one divine, for a man to come under promise to another master after Christ, and to abjure father, mother, and all nearest kinsfolk, whom even the law has commanded us to honour and love next to God Himself, to whom the gospel, too, holding them only of less account than Christ, has in like manner rendered honour? Shall it be held lawful to make an occupation of the sword, when the Lord proclaims that he who uses the sword shall perish by the sword? And shall the son of peace take part in the battle when it does not become him even to sue at law? And shall he apply the chain, and the prison, and the torture, and the punishment, who is not the avenger even of his own wrongs? Shall he, forsooth, either keep watch-service for others more than for Christ, or shall he do it on the Lord’s day, when he does not even do it for Christ Himself? And shall he keep guard before the temples which he has renounced? And shall he take a meal where the apostle has forbidden him? And shall he diligently protect by night those whom in the day-time he has put to flight by his exorcisms, leaning and resting on the spear the while with which Christ’s side was pierced? Shall he carry a flag, too, hostile to Christ? And shall he ask a watchword from the emperor who has already received one from God? Shall he be disturbed in death by the trumpet of the trumpeter, who expects to be aroused by the angel’s trump? And shall the Christian be burned according to camp rule, when he was not permitted to burn incense to an idol, when to him Christ remitted the punishment of fire? Then how many other offences there are involved in the performances of camp offices, which we must hold to involve a transgression of God’s law, you may see by a slight survey. The very carrying of the name over from the camp of light to the camp of darkness is a violation of it. Of course, if faith comes later, and finds any preoccupied with military service, their case is different…”

Again, pacifism and the forbidding of military service is more of an interesting footnote than it is the subject of this essay. To get us back on track…

What Changed?

Early Christianity had a strong democratic and anti-aristocratic undercurrent to its framework. Roman aristocracy had already been receiving pressure from its underclass, with Christianity promoting such a worldview this only increased. The Roman state became beholden to the Bishops in a way unimaginable to previous generations; the state had always maintained a large degree of control over Paganism, even when accounting for mystery cults.

This democratic force was, in fact, used. Emperor Theodosius was forced by the Bishop of Milan to pay public penance before he could reenter communion [Chapter 17] after a massacre was ordered in consequence for a riot. One of the reasons why Theodosius caved to these demands was out of fear that the Bishop could mobilize the populace against him. Democratic force was a key feature in the end of several emperors’ reigns; the fear of it was not unjustified. While in previous centuries the mob was best controlled by patronage, after Constantine it was largely in the control of the Bishops. This dynamic remained until the fall of the Western empire.

However, this new religion, in becoming a part of the state, now had to face realities which it had not as a minority. The state, being the new defender of the power of the Church, was no longer a force of opposition. This meant that the Church was now in the business of earthly government as well as spiritual salvation. The promised apocalypse had still not manifested. Barbarians, many still Pagan, were at the empire’s doorstep.

Dialogue of sharing all things in common was gone, in its place was a much less radical form of charity. Wealth inequality was treated as much less concerning, now poverty was the enemy. Some level of martial prestige had to be preserved in order to maintain an army capable of the defense of Rome and her borders.

Christianity was still a powerful force, but its early zealotry had been compromised in order to maintain the earthly affairs which the Church was now entangled with. This is not to say that either the Church or Christians at large were less faithful to their practice, but rather that they were forced to accept that the realities of their time required governance which was rooted in that time, not in an idealized future.

This created a balance of power. The Roman nobility and the Emperor required the power of the Church to control the masses, which once again were a real threat at this time in history. The Church accomplished this through the use of morality, allowing nobles to exchange the patronage system for charity and displays of virtue. In turn, the Church required the force of the Roman state to defend its borders and maintain the infrastructure which the Church needed in order to spread its religion.

This does not mean that the two forces did not continue to jockey for power. As we will see in the next piece, the Church and the various states of Western Europe find themselves with opposing goals quite often throughout the Medieval period. However, the two are more aligned than they are in conflict, particularly after the conversion of most of Europe. This power dynamic is a primary characteristic of what we know as “the West”, and it remains, (albeit in a much different form), even today.

Closing Thoughts

It is impossible to overstate the effect which Christianity had on the moral framework of Western Europe. The shift can only be described as revolutionary.

The focal point of value in antiquity can best be described as vitality. Nearly all Greek myth is concerned with heroic individuals accomplishing great feats and gaining power through these actions. Additionally, Greek myth was greatly concerned with one’s blood, (Miasma often followed entire family lines, as in the myth of Oedipus). Germanic and Celtic myths followed similar trajectories. Many of these individuals are supposed to have created lineages, which, (although somewhat mythological), formed the beginning of long family genealogies. If the ancient world’s religious worship can be boiled down to one thing, it is the worship of greatness.

Christianity turned this on its head. The fundamental premise of Christianity is man’s equality before God, regardless of his bloodline or vitality. Modesty and humility became virtues, pride became a vice. Martial character, while not explicitly frowned upon within the gospel, became a sort of vice because it was historically tied to an aristocracy which practiced an opposing sort of morality and was seen as oppressive.

The entire moral framework in which modern Westerners reside in is based on Christian ideas. All anti-egalitarian premises remaining within the West are based on only two foundations: the idea of the “Protestant work ethic”, (to be discussed), and much older concepts of blood and aristocracy. The latter of these finds itself constantly on the defensive, as even the idea of genetics is under attack within modernity. Additionally, the idea of work ethic is now controversial in some elite circles within the West.

In short, the very idea of what is “good” now would be relatively foreign to most pre-Christian thinkers. For the pre-Christian, the “good” would have been synonymous with the “great” or the “noble”. The closest comparison is the idea of “justice”, but this idea was far different in antiquity than the modern understanding, and certainly different from the idea of being “good”. The idea of “good” and “evil” as two coherent and opposing forces is one which was only introduced in its modern form after the advent of Christianity.

Thank you all for reading. With this piece in addition to the last, we have a good understanding of the dynamics whose interplay defines “the West”. This understanding will allow us to get much deeper underlying phenomena which both consist of and cause politics.

TLDR?

How many installments will there be?